The Blackburns: Private Lives, Public Ambitions

This month sees the publication of historian Carolyn Rasmussen’s latest book, a fascinating dual biography of two idealistic activists and partners.

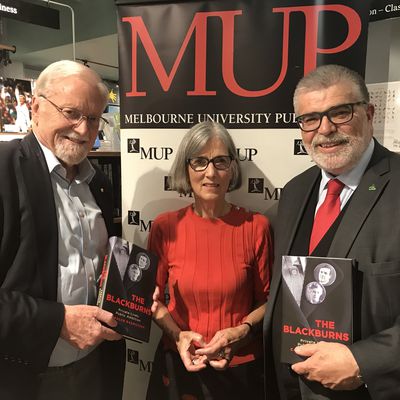

MUP authors Gareth Evans AC QC, Dr Carolyn Rasmussen and Sen Hon Kim Carr at the Readings launch of The Blackburns.

Last night, the Senator the Hon Kim Carr launched Carolyn Rasmussen’s The Blackburns: Private Lives, Public Ambition describing it as ‘a highly accessible read for anyone who cares enough about politics to want to go beyond what is served up by the daily media... [this] book continues MUP’s long tradition of being Australia’s pre-eminent publisher of historical works.’

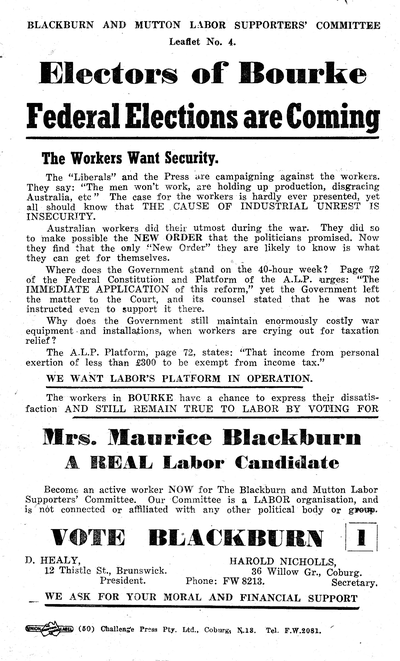

In this fascinating dual biography, Carolyn Rasmussen rescues Maurice and Doris Blackburn (nee Horden) from the footnotes of history. ‘By making Maurice and Doris the joint subjects of this biography, Carolyn has rightly rejected an earlier tendency in some quarters to emphasise Maurice’s achievements, and to see Doris chiefly as an understudy. Doris was politically aware and active before her marriage to Maurice, having worked as campaign secretary for Vida Goldstein in the Women’s Political Association. This book has been seen in some quarters as a love story. What is important to stress, I think, is that the Blackburns had a genuine partnership, politically as well as domestically.’ said Kim Carr.

When socialist barrister and aspiring member of parliament Maurice Blackburn met Doris Hordern, ardent feminist and campaign secretary to Vida Goldstein, neither had marriage in their imagined futures. But they fell in love—with each other as much as with their individual aspirations to change the world for the better. Theirs would be an exacting partnership as they held one another to the highest ideals. They worked as elected members of parliaments and community activists, influencing conscription laws, benefits for working men and women, atomic bomb tests, civil rights and Indigenous recognition. Together, they shook Australia.

Earlier this month, on International Women’s Day, Carolyn Rasmussen spoke at the Maurice Blackburn law firm in Melbourne, as it celebrates it’s 100th anniversary. In the spirit of IWD, Carolyn took the chance to channel Doris, ‘conjuring up her restless spirit for a few moments to inspire the minds and hearts of a group who continue to give substance to the dream she shared with her husband, Maurice Blackburn... the dream of making the world fairer and more peaceful’.

Here is the speech Carolyn gave:

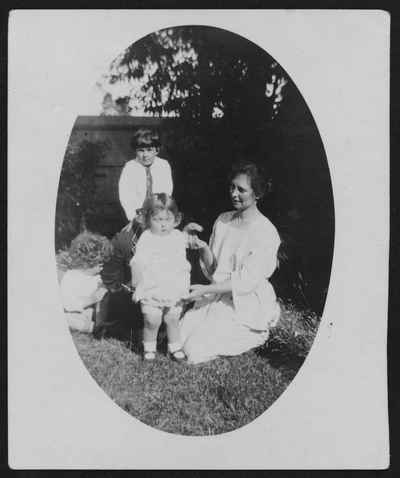

International Women’s Day is, at its core, a day that recognises rebellion and uplifts radical demands for equality. It was a day of great significance for Doris Blackburn, a life-long campaigner for women’s rights, but also a woman of the left, for whom International Women’s Day has a long history. The first women’s national day was organised by the Socialist Party of America in 1909 to commemorate the huge New York garment workers strike the previous year. The first International Women’s Day in Australia was celebrated in 1928, with a rally in Sydney's Domain, organised by the Militant Women's Group of the Communist Party. As a result the day remained ‘tainted’ in the minds of many until the 1970s when a new wave of woman activists embraced it. So, it’s important to note that Doris’s role in the organisation and activities of International Women’s Day in the middle of last century was a doubly radical act of rebellion against the status quo. She was a woman active in public life at a time when women were still much discriminated against in that arena—as well in the workplace, and she was an outspoken advocate for causes and groups which were considered deeply suspect as the cold war freeze set in. When, for example, in 1955 Federal Parliament was presented with a petition of 14,000 names opposing the testing of atom bombs, 200 of them had been collected at an IWD celebration in the Lower Melbourne Town Hall which Doris had addressed. Doris’s standard address to such gatherings usually focussed on something along the lines of ‘women’s progress towards equality’. She was after all an optimist – an essential quality in someone who had been campaigning for women’s rights since 1911 when she joined the Women’s Political Association as a twenty-two-year old. She managed well-known suffragette Vida Goldstein’s campaign for the federal seat of Kooyong in 1913, followed by active involvement in the anti-conscription campaigns and the peace movement during World War One. While her children were small in the 1920s she combined serious study of social psychology with activity in the progressive education movement, before emerging as a formidable advocate for peace through collective security in the 1930s. Then in the wake of Maurice Blackburn’s loss of the blue-ribbon Labor federal seat of Bourke in 1943 and his death soon after, she reclaimed the seat as an Independent Labor Candidate in 1946.

Now let me shift gear and try to add some nuance that to picture of Doris—the social and political activist.

Let’s start with the feisty girl—about grade 6 I would say—who flicked a folded note across the classroom to her friend Dorothy who had just been chastised by their teacher. ‘Don’t worry about her’, she wrote, ‘she’s a fat pig’! Unfortunately, the note was intercepted and ‘wicked’ Doris was hauled before a general Assembly and the girls were instructed to pray for her. Her outraged father took Doris away from that school—and sent her to Hessle, a progressive ladies college where she came under the influence of two feminists—one of whom would introduce her to the Women’s Political Association and in some ways her life course was set.

Doris excelled at drawing and English, but she was no slouch with numbers either—certainly not when it came to budgeting. Her senior school essays show maturity and a persuasive flair. She loved reading and poetry and aspired to be published. She had two poetic voices—a sentimental Edwardian one that dwelt on children in the garden, fairies gathering dewdrops and such like—and a modern one that could be sharply observant, ironic or introspective. Both the emotional and the political Doris is present in these poems. ‘I will build my house on a hill top’, she wrote, ‘But do not expect me to sit in contentment’. There were too many wrongs to be righted. She tried her hand at short stories and film scripts, too. She had a keen ear for the spoken word. The quality of her articles, reports and speeches are buttressed by this literary sensibility, coupled with painstaking research and measured argument. Doris had taken out a teaching certificate. To this she added extended training in debating with a Melbourne group ‘The Wranglers’. And yet Doris would feel keenly to the very end of her life that she was insufficiently educated.

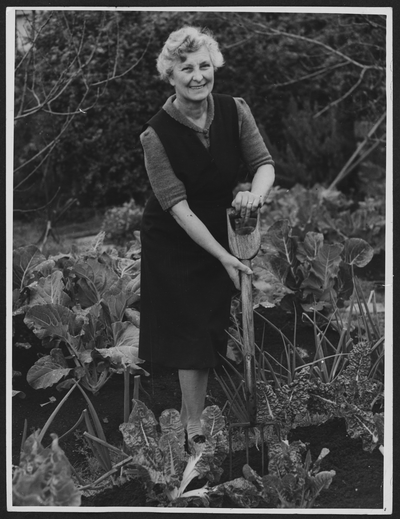

Doris was an exuberant and energetic woman, at home riding a horse or rowing against tidal currents in her early years. She had great capacity for self-control and organisation—and considerable skill in gardening, and the domestic arts. But there was a wild Doris always threatening to break out. She felt a powerful pull of ‘nature’, especially of mountains and the sea. Like many feminists of her generation, she was a proto-conservationist. This was a woman who loved to run outside and get thoroughly wet in those wild thunderstorms that break across Melbourne at the end of a heatwave. ‘Come away!, she pleaded in another poem, ‘come away’ to dance in ‘the paradise where sand and waters meet’. But there would be no actual running away – her words and her energy were marshalled to work for important causes. Though she had not expected to marry, in Maurice Blackburn Doris found not just a lover but a political soul mate, who was as passionate about women’s rights as she was, as well as the needs of the poor and the powerless. The idealistic Doris assured him that she had no desire for worldly goods. Her principal wish was that he 'should help in the struggle for freedom and advancement' for neither of them could 'shut [their] eyes to suffering & oppression'.

Marriage and children did entail putting aside her own ambitions for a time, but it was the Great War that added the most significant new element in her political ambition – to bring an end to war. Nowhere is this better expressed than in one her most powerful poems, written in 1916 on discovering that her favourite cousin had been killed – only a few months after the death of two of his brothers in the battle of the Somme. It’s called ‘O Woman Awake!’ and I’ll just quote a few lines to give you the flavour – since its meter is not up to her usual standard:

The world is ablaze

There’s blood on the earth

There is blood on the sea

Oh see! It’s your heart’s blood that ran in the veins of your children!

Oh, woman awake!

Rise up from your slumbers and hold them

The blood is your own

It’s the life that you gave to your children.

That call, ‘O, woman awake’, she would continue to make in one form or another till she drew her last breath. Not just in matters of peace—but in matters of justice and equality—for she saw women as important agents of their own destiny – and to a large extent her principal role was to ‘wake them up’ – to enlist them in the work of creating a better place for all humanity. And that is, of course, the call she would still be making on this International Woman’s Day if she were here.

In the 1920s, while Maurice put the finishing touches on the removal of the last remaining obstacles to the full participation of woman in public life, her personal campaigning shifted not to ‘mothers and babies’ as was the case with many feminists, but to progressive education. It was at base, still peace work. Essentially Doris believed that children schooled in a less rigid and competitive environment, full of outdoor play, art and music and free of war toys, would develop the social consciousness and humanity that would make wars less likely in the future. But that was a long term project. She was still mounting platforms to speak against war toys in the mid 1960s—but as the war clouds gathered on the European horizon and her children reached adolescence, she turned her attention more explicitly to trying to head off the second world war thought her work in the International Peace Campaign, where, you won’t be surprised to know, she took charge of the Women’s Commission. Always, the call was to women to rouse themselves, to realise the power the vote had given them. And she was always there to help women in practical ways—as when the women in her neighbourhood, frustrated with their efforts to get facilities for children that would free them for war work, approached her for help to build a kindergarten.

For Doris, who would henceforth take every opportunity to slip in and spend some time with the children, this was more than a kindergarten. It was also a forum to educate women in how to get things done for themselves and how to keep what they achieved. As she wrote to her daughter from London in 1952, on hearing that there was some trouble brewing there, ‘it may do them good to learn something of government and departmental methods. When they had nothing they could get no assistance for the care of their children. When they have built a good Kindergarten and it is completely free of debt owing to their own efforts it will be taken away from them ... Perhaps such lessons are needed to rouse all women from their political apathy’. And so when the possibility of trail blazing into Federal parliament came up—Doris immediately grasped the opportunity to set an example to a generation of women in whom she was just a little bit disappointed. Looking back on the early days of the Women’s Movement in which she had played some part, she observed, the women ‘were enthusiastic. They worked like tigers. In the generation that followed they seemed to grow lazy politically’.

In federal parliament Doris joined Edith Lyons as the second woman to sit in the House of Representatives, where she is most remembered for her eloquent and courageous stand against the Woomera Rocket Range—not only for the dangers it posed to the local Aboriginal communities, but also as a critical element in an escalating arms race that was a serious threat to world peace. More broadly, Doris was primarily committed to carry on Maurice’s work because she fully shared his commitment to principle, and to the ideals and aspirations of the labour movement. Her focus in parliament, whenever she could get a word in, was a 40 hour week, a national emergency housing program, endowment for the first child, taxation reduction, full employment and a better deal for pensioners. In international affairs, she worked to rouse the Australian people to take a ‘more noticeable interest in overseas’. ‘Like her husband’, she stood for ‘justice and tolerance for religious, political and racial minorities, both at home and abroad’. She also worked for ‘a better deal for the Aborigines at home, and adequate rehabilitation for the war-sufferers overseas’. She also emerged as a relentless voice seeking improvement in the conditions of employment of women in the Commonwealth Public Service.

When she lost her seat in parliament in 1949, caught in the wave that swept Chifley’s progressive post-war Labor Government from power, she took her much enhanced public profile back into work for international peace, and a range of other issues such as capital punishment, the treatment of women prisoners, civil liberties generally, but most especially she applied her energies to securing civil and economic justice for Aborigines, primarily though her role in the Aborigines Advancement League which she co-founded with Gordon Bryant in 1957 and support for the hostel for Aboriginal Girls in Northcote. This might be the moment to note her life-long prodigious contribution to fund-raising stalls—not only pounds and pounds of jams—notably marmalade—but produce from her garden, herbs, potted plants and handicrafts.

Until only weeks before her death at 81 she was willing to speak wherever and whenever she was asked, on topics that covered her wide interests in social reform, education, international relations and indigenous rights. This activity was underpinned by her philosophy of ‘chipping away’ at influencing public opinion on the big issues of the day, but also seeking to educate and empower women whose work was largely invisible and undervalued.

So, I will end with what I believe would be her message if she were here today. She would applaud and detail the progress. She would be especially pleased with the number of Labor women in parliament, but she would see that there was still a way to go—and that would require unceasing effort and vigilance from women themselves, in spite of the obstacles, and their tendency to ‘belittle’ their own work. But, she would caution against the value of a purely ‘women’s ticket’. Her own life was testament to her belief that women ‘should work with men as partners for the common good’.