Monica Dux pays tribute to Hannah Robert's memoir of loss and grief

"There’s an awful contradiction in the loss of a baby."

Writer Monica Dux pays tribute to Hannah Robert's memoir Baby Lost, touching on the contradictory nature of losing a baby, the acknowledgement of grief and the way Hannah's story gives voice to something often experienced in painful silence.

I first met Hannah nearly two decades ago when we were postgrads at Melbourne Uni. Hannah is the sort of person you can’t fail to notice: engaging, vibrant, friendly, and with a luminous intelligence.

I didn’t see Hannah for a few years after my postgrad days, but I always remembered her.

I also remember the moment in late 2009, when I was nursing my newborn daughter, and I read on Facebook that something very bad had happened to Hannah. That she’d been in a car accident, and her baby, who she was 8 months pregnant with, had died.

I know a lot of people in Hannah’s circle, and outside it, people like me who’d not seen her for ages, would have been affected, as I was, by the loss of Hannah’s daughter. It wasn’t just that someone we knew had a terrible tragedy befall them. It was the nature of that tragedy.

There’s an awful contradiction in the loss of a baby.

These stories don’t fit neatly into how we understand the sequence of the two events that bookmark our lives. Birth and death are not meant to be so intimately twined, so contracted, and yet when they are, it leaves behind an inscrutable paradox that makes this sort of loss and the grief that accompanies it unique.

There’s often a reticence to talk about the death of a baby. The irony in this reluctance is it’s not really that uncommon. It doesn’t take too much effort to find someone who has lost a baby, a longed for pregnancy, or even a child.

Yet perhaps because of their seemingly inexplicable nature, we treat these losses as if discussion of them and their aftermath is taboo, leaving grief that is to be locked away, not spoken about, and far too often ignored. These deaths make us uncomfortable, we don’t know exactly what to say. Often, people have no idea just what has been lost, and what is being grieved, and the silence only serves to further encourage that.

Just under a year after Hannah’s accident I was on a panel at the Melbourne Writers Festival and Hannah came up to me afterwards. It was the first time I’d seen her in years, and although I’m sure she wouldn’t remember the event, I remember it vividly. I said I was so sorry for what had happened to her, and she responded by talking to me about the importance of acknowledging the grief that accompanies the loss of a baby. I’d published an article in the newspaper about a miscarriage I’d had, and Hannah had read it. I think by that point she’d read just about everything she could on pregnancy loss, and she wanted to talk to me about it.

I recall being amazed by Hannah’s poise and her determination; it was that same luminous intelligence, and vibrancy that I’d remembered from all those years before at Uni.

So when I put together Mothermorphosis, a collection of essays I edited about the experience of becoming a mother, Hannah came immediately to mind. I knew she was a wonderful writer. I also knew she had a story to tell, and the courage and clarity to tell it. Her subsequent essay was one of the triggers for her to write this book.

The piece she wrote for Mothermorphosis was exquisite.

Her grief was so palpable on the page, so crystal-clear, that it was hard to read her drafts without being reduced every time to a puddle of tears.

And yet, it wasn’t just the weightiness of grief that she articulated so well.

What struck me most about Hannah’s writing was the way her beautiful daughter Zainab, with her “round cheeks, dark hair and her pointy little Rima chin” became so very present on those pages. Hannah’s lost baby was not reduced to an unknown possibility, a two dimensional object of her sadness. Zainab was an active participant in Hannah’s tale. She was whole, she was formed, she was beautiful and as dynamically present in that story as she had been so present within Hannah during her pregnancy.

What Hannah’s book articulates so gloriously, and so poignantly, is that at the heart of the loss of a baby, there is a very real, enduring presence, a presence that permanently reshapes those left behind.

“Lost” is a tricky word to use in this context; a baby that never takes a breath, the loss of a pregnancy, the loss of a baby. It sounds as if there was some mishap, a carelessness, and you only need to locate the lost again, somewhere.

But “Lost” is an apt way to describe so much of what happened to Hannah, and also to her baby, after the accident. Hannah wakes up into a world that seems alien to her. And her journey is about reconnecting and re-entering the world, but also finding the baby that died, working out where she went, and how to live with her absence, while realising her presence.

Hannah writes about a friend who’d lost a baby years before she did. “There was something completely unquantifiable about the loss, and the gain, which a stillborn child brought”.

And that’s the magic in Hannah’s writing. I could say it’s brute talent, brilliance or skill (which it also is), but I think it’s apt here to use that woo woo word, magic, because it evokes an unknowingness, a sense of wisdom, and her ability to articulate that most unquantifiable loss, and bring it into the light.

It’s very hard to do justice to Hannah’s book without reaching for weighty words: searing, touching, heart-felt, courageous, devastating, gutsy, heartbreaking.

These are powerful words, epic words, for what is an epic story, but one experienced every day by so many parents as they grapple with such loss. The absolute gift of Hannah’s writing, and of this book, is that she takes all of this loss, and offers it up to the reader, giving a voice to what so often is left in painful silence. She does so with courage and grace, refusing to end the story with the end of her baby’s life.

In the final pages, Hannah writes:

“Whatever your loss, I want to make it easier for you, to help you short-cut through the pain and the banging of one’s head against the finality of death. But my mechanics work because I have crafted them from my own head, custom-built them around my irregularly shaped heart. Yours will be different, Just know I am here with you, holding the torch.”

I know there will be so many, many people grateful for Hannah’s book, and for her choosing to hold the torch with them.

This is an edited version of the speech Monica Dux gave at the launch of Baby Lost at Readings Hawthorn.

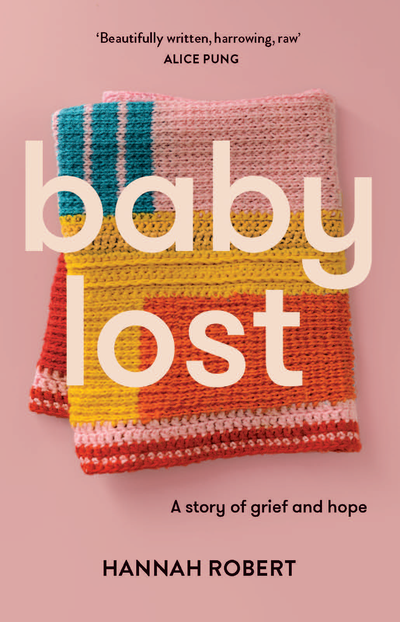

Baby Lost is out now.