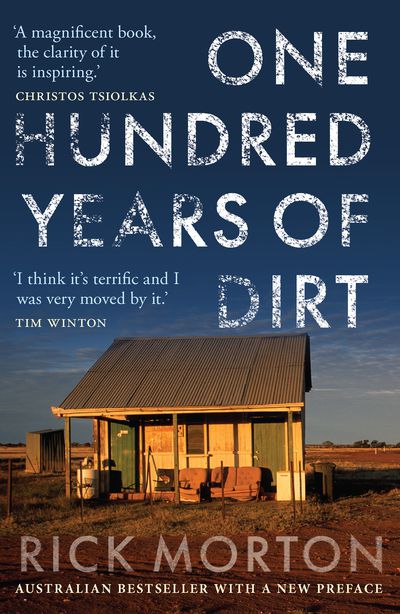

In this extract from One Hundred Years of Dirt, Rick Morton writes, the only inheritance was fear and despair.

In the beginning, my family owned 0.4 per cent of the entire Australian landmass. This is quite a lot. Indeed, it is very big. My grandfather, George Morton, and his family possessed five cattle stations collectively the size of Belgium — 30,000 square kilometres — in the kind of country known for killing lost European tourists. The flagship was Pandie Pandie Station, 6625 square kilometres of stony claypan just south of the Queensland-South Australia border, off the Birdsville Track.

It took a particular type of person to live there. The landscape was vicious and largely incompatible with life. During the violent dust storms that brewed in the Simpson Desert 100km to the west, the tops of sand dunes, themselves 30m high, would be whipped off and carted east. Life stopped when these storms swept in, dumping sand through every opening in the homestead. The wind moved the desert indoors and it would need to be taken out again, not by dustpan and broom but with shovel and wheelbarrow.

“There are stories of weak, thirsty cattle being covered where they lay, of stockmen lost between cattle yards and the dinner camp,” local historian Lois Litchfield writes in her book on the region, Marree and the Tracks Beyond. “The devastating sensation of checking a sleeping baby in his cot, only to find him completely covered with sand, ears and eye sockets…