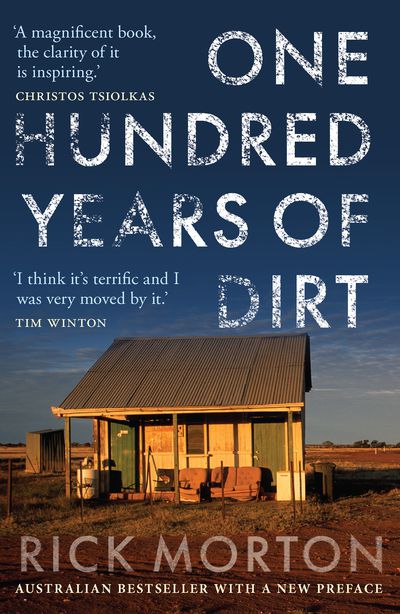

←Back to One Hundred Years of Dirt

An extract from “One Hundred Years of Dirt”

In this extract from One Hundred Years of Dirt, Rick Morton writes, the only inheritance was fear and despair. Read the entire extract over at The Australian.

In the beginning, my family owned 0.4 per cent of the entire Australian landmass. This is quite a lot. Indeed, it is very big. My grandfather, George Morton, and his family possessed five cattle stations collectively the size of Belgium — 30,000 square kilometres — in the kind of country known for killing lost European tourists. The flagship was Pandie Pandie Station, 6625 square kilometres of stony claypan just south of the Queensland-South Australia border, off the Birdsville Track.

It took a particular type of person to live there. The landscape was vicious and largely incompatible with life. During the violent dust storms that brewed in the Simpson Desert 100km to the west, the tops of sand dunes, themselves 30m high, would be whipped off and carted east. Life stopped when these storms swept in, dumping sand through every opening in the homestead. The wind moved the desert indoors and it would need to be taken out again, not by dustpan and broom but with shovel and wheelbarrow.

“There are stories of weak, thirsty cattle being covered where they lay, of stockmen lost between cattle yards and the dinner camp,” local historian Lois Litchfield writes in her book on the region, Marree and the Tracks Beyond. “The devastating sensation of checking a sleeping baby in his cot, only to find him completely covered with sand, ears and eye sockets full, as though he’d been there for months rather than minutes.”

Here, on these torrid plains, my grandfather George began one of Australia’s longest-running border disputes with his neighbour Lyle, who also happened to be his brother. What follows is fortunately the subject of newspaper record, else it could scarcely be believed.

The year is 1973 and Lyle Morton, a sensible man, apparently agreed with my grandfather to build a boundary fence, which ran the 40km between their two stations, Roseberth and Pandie Pandie. The stations had once been a single sprawling behemoth but were now being run separately. Lyle’s estimation of the subsequent falling out, in the pages of The Australian in 2002, was precise: “He wouldn’t pay for his half of the f..kin’ fence.” The punch-up that followed at the Birdsville Hotel is still the stuff of local legend.

Here the story enters bizarre territory. According to Lyle, the once-in-a-generation floods that swept Queensland in 1974 knocked out the boundary fence. “So I told the f..kin’ bastard it was his turn to build another one,” he told the newspaper. “He refused, so I built me own fence, [200m] away from the boundary. To get back at me, the f..kin’ bastard built his own fence along the boundary. The area in between is no-man’s land.”

The “demilitarised zone” as Lyle called it — all 12 square kilometres of it — remained until my grandfather’s death more than 30 years later. Both fences are still standing, maintained by my father’s cousin on one side and my cousin on the other. When last quizzed about this extraordinary act of intransigence almost three decades after the argument began, my grandfather wasted little time on it. “It’s that bloody stupid I don’t want to talk about it. He’s [Lyle’s] as silly as a f..kin’ wheel,” George told The Australian. “There was never any f..kin’ problem. He was just adamant that he wanted to put up another fence. There was no f..kin’ problem.”

George Villiers Morton was a hefty and intimidating man. He had those Morton bones, as if they had been petrified first before the flesh was sewn on. He owned every room he ever walked into and seldom had to enforce the terms of his presence.

The Mortons had been on the Birdsville Track since the turn of the century. It was theirs. A plausible explanation for the colony’s failure to launch a carbon copy of class as it was once known on milder shores is that great, yawning interior of the Australian continent and a distinct lack of hands. The need to survive required mutation. There was work to be done and free landholders couldn’t afford to sit back and issue orders from the sidelines. These typically highborn squatters became, in effect, Australia’s landed gentry but with a much more practical flourish. It was into such a family, quite some time later, that I was born.

In a way, we were caught between the inherited mistakes of the Empire. Our cattle station, like many others, was overrun by introduced species, and my father Rodney’s idea of himself was tangled up in the need to have his own vast property. But solving the problem of the Morton family’s diminishing status was not that simple. Rodney was the second-youngest of George’s seven children and competed admirably for the position of least favourite. Despite his parents owning sprawling pastoral titles across four states and territories, there would be no property held for him.