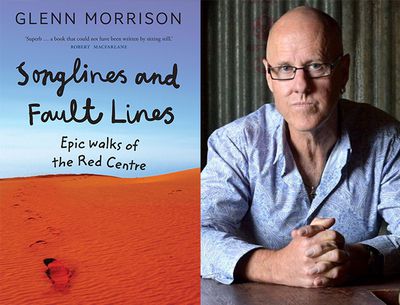

Songlines, Fault Lines and Literature

Q&A with author Glenn Morrison

Songlines and Fault Lines explores the intriguing stories of six epic walks in the Red Centre of Australia, while exploring topics of wilderness, colonialism, belonging and Indigenous cultures in Central Australia.

In this Q&A author Glenn Morrison discusses the places and stories that inspired his book; finding similarities between white and Aboriginal cultures through walking; seeking ‘wildness’ as a respite from the modern world; Bruce Chatwin's seminal The Songlines thirty years on; and some favourite Red Centre walks and places.

Why did you decide to write this book about walking?

I guess I just fell into the walking narrative thing, but it certainly sparked some fortuitous coincidences.

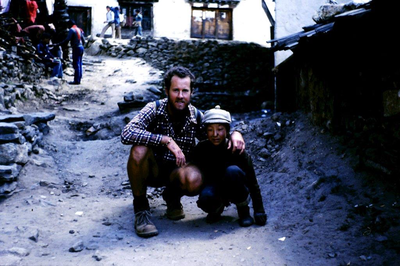

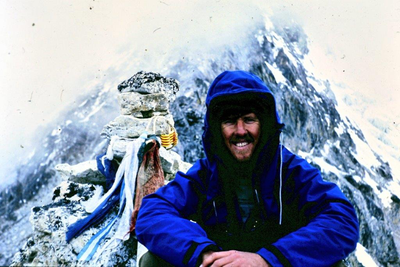

I’ve been an avid walker since I was a boy; pretty much spent my whole childhood roaming the bushland of the Georges River National Park in Sydney’s south-west, which I accessed thanks to a couple of palings missing from my parents' back fence. And I loved reading walking narratives from early on: Ed Hillary, Peter Mattheisson, ‘boy’s own’ style adventures. I once met Hillary while walking in Nepal, I was so excited… but that’s another story.

I had wanted to write a non-fiction portrait of Alice Springs and the Centre, so had been fielding around for books that might inspire. My feeling of having arrived in Alice Springs as some sort of ‘coming home’ was difficult to explain in the face of its reputation as a hard-drinking, tough and violent frontier town. It seems to be positioned not only at the centre of the Australian geography, but also at the heart of a discourse around reconciliation between Aboriginal and settler Australians. Moreover, the sort of narrative portrait I envisaged for the Centre is rare when it comes to Australian cities and places, compared with, say, the U.S. Of course I’d be proven wrong with just a few exceptional examples: Ruth Park’s slum life of Sydney, Charmian Cliff’s short essays of place and travel including the Centre, more recently Mark Tredinnick’s Blue Plateau about the Blue Mountains near Sydney. Also, New South’s ‘Cities’ series, which asked prominent authors to write about their hometowns. All of these certainly gave some clues… but I wanted to combine a ‘feeling’ sense of place with the complex politics around me.

The first book that really got me thinking about the Centre and walking was, oddly enough, Bill Bryson’s A Walk in the Woods. As well as being an entertaining read, it manages to examine some of the pressing social and political issues facing America. Bryson’s is a walk of the Appalachian Trail, which traces the east coast of North America. There was perhaps an obvious parallel to be drawn with the Larapinta Trail, which stretches 223km from Alice Springs west to Mt Sonder in the West McDonnell Ranges. But I was also taken with those who’d walked the city: Virginia Woolf, some of the journalism of Charles Dickens, Delia Falconer does a little in her portrait of Sydney. I stumbled across the British psychogeographers who probe how their psychology intersects with the places they walk, Will Self and Iain Sinclair for example. Then Raja Shehadeh, the Palestinian lawyer who walked the hills of his home as a way of examining the lawfulness and morality of Israel’s encroachment upon Palestinian lands, but also to explain exactly why he loves those hills so much. Shehadeh really resonated.

In the end it came down to something I already felt quite strongly, which was, as I say in the book, that I don’t really feel comfortable in a place until I’ve walked it. Walking is a way of mapping the world around us in our minds, of knowing the world through the feet. And this idea is expressed so strongly in the Aboriginal Dreaming Tracks, or the ‘songlines’ as Bruce Chatwin called them. They are a storied map of the landscape, locating points of significance and a safe route across an arid landscape, corridors of trade in a walking economy. By knowing the right stories, a walker could find their way clear across the country.

So structurally speaking, walking is also a handy way to unpack the various received wisdoms about a place, while at the same time exploring its physical beauty or otherwise, the affect of the place, as geographers call it. As well as being a mindful thing to do, walking puts you intimately in touch with your environment, whereas driving around, say, is more like so much television. I guess that was the key to the whole thing, what led me to start doing a series of walks to explain my home to myself, as much as to anyone else.

Actually, only a few of those stories of walks made it into the book. Along the way I was struck by the notion that walking was something shared between Aboriginal and settler, and that comparing walking stories between the cultures might allow me to explore similarities, rather than the differences so often emphasised. So I started to critique those who’d walked the Centre before me. In the end I combined my own walks of the Centre with those of literary figures gone before. The result was Songlines and Fault Lines.

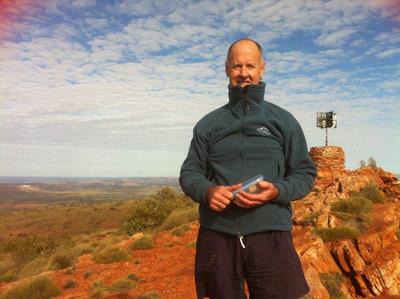

What do you enjoy most about walking in Central Australia?

The sense of space. The bare rock. I’ve always been a bit of a geology freak, although these days I’ve probably forgotten most of it. But I still love the feel of giant spires of jagged rock, the peaks and gorges, the waterholes and swimming in them and splashing around at the base of towering cliffs. There’s a sense of adventure to be had just by looking at the landscape.

And there’s a clear sense of freedom of movement in and over space. I found the same scuba diving in my 20s: I was more enchanted by the grandeur of a deep ravine as it unfolded before me under the water, than by the minutiae of a place, although that was pretty good too.

And the air. It’s dry, fresh, unassuming. There is a sense of wonder here, as if the world began only moments before. But there’s also the knowledge of those who have gone before… their presence is everywhere, there are so many layers to what you see in the Centre.

But perhaps most of all, it is culturally compelling, living on the edge of and among another culture, and one so significant and fundamental to any ideas of an ‘Australian’ story, but also one sadly neglected. I feel for the tourist who comes to the Centre expecting the Romantic. They’ll find that, but they'll also find the apparent social chaos that is sometimes Alice Springs. They become confused, disappointed that the books were maybe wrong. Or so they think, but that’s largely what they take away. But there’s so much more. And that’s one of the pivotal motivations for the book, a sort of ‘don’t judge a book by its cover’ philosophy, here’s a bit more of the story, my bid to explain why it is like it is.

Many of the walkers you write about run into dire trouble on their travels. Have you ever been in a sticky situation when out on a walk?

There’s been a few I guess. But I’d preface anything by saying I’m not particularly adventurous when it comes to risking my neck. I’m definitely one to be wary and go for a middle option, rather than take risks for the hell of it.

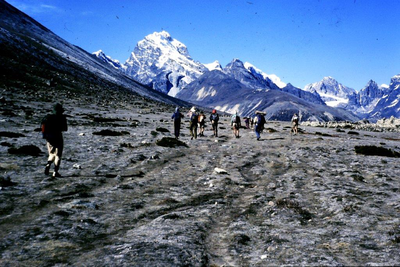

My longest walk was about 35 days across Nepal in 1986. By comparison the Centre’s Larapinta Trail, of which I’ve only done bits by the way, is 15–20 days, although I know some have done it in a remarkable 11. In Nepal, we actually started from India where it’s all hot, humid plains and walked to near the Tibetan border at Kala Patthar, where it’s all ice and rock. Kala Patthar actually means ‘black rock’, and is an easily climbable peak for those without mountaineering skills. The summit is at the foot of Mt Pumori, and from there you get stunning views of Everest and neighbouring Lhotse and Nuptse. But before you picture me as some intrepid mountaineer, there was no technical climbing per se, more a lot of huffing and scrambling. And it was all done with friendly Sherpas carrying much of our gear and serving you tea first thing in the morning!

Kala Patthar is at roughly 5570 metres altitude, and despite our gradual climb from the grasslands and jungle near sea level through the cloud forests, to the glacial Khumbu, I teetered on the verge of altitude illness the whole time I was above Lobuche, the last settlement on the way up. We camped at Gorak Shep, which in the 1950s had been the original base camp for Everest climbers. It was cold: plunged to –20°C overnight and my sleeping bag was sorely tested. Moreover, the weather was predicted to close in fast next morning.

Bearing in mind you never sleep long or well at altitude, we rose about 2am to begin the climb to Kala Patthar. There is a large lake bed to cross that can be best described as lunar, then a series of switchbacks to climb and finally a gravel and rock-strewn slope to climb to the summit. This last was pure hell for me.

A thick cloud bank chased us up the mountain toward dawn, but held off long enough for us to get a clear look at Everest. But the last stretch was steep, the air painfully thin, and my head sludgy and pounding from the altitude, like someone with a hammer was trapped inside and trying to get out. The howl of the wind prevented anyone speaking at anything less than a desperate shout, so for most of the walk talking was impossible. Breathing was all I could manage, and that came in unsatisfying gasps, a real fight for oxygen. Two or three steps forward, stop for breath, panting as if I had sprinted a hundred metre dash. Looking back, I think I’d overdone it on a sort of training climb a couple days earlier, which had left me feeling pretty raw.

As I struggled forward in my own private hell, I wondered how on earth Hillary and hundreds of others since had climbed a further ten thousand feet to the summit of Everest, which I would struggle to even peer up at.

Somewhere around then two Tibetans from our crew came hurrying down the mountain carrying another Sherpa on a stretcher. Having succumbed to altitude illness, the man had to be despatched immediately to lower altitudes at all speed, or risk death. He was in good hands, but the incident didn’t fill me with confidence about my own ability to stave off the same fate. Underpinning my declining sense of well-being, I’d had dysentery for most of the month prior and don’t mind saying that for the first few weeks of the trek I’d felt dreadful. Now my head was screaming to boot and my chest burned with every gulp of the freezing air.

But I kept on, and step by step reached the summit. It was a knife edge of rock plunging thousands of feet into sheer nothingness beyond. But sitting down on that rock was bliss. And the view and elation at having made it were totally worth it. Later I learned several walkers from our group had turned back that day from altitude illness. The affliction remains a mystery to me, as to where and why it strikes. I felt lucky I had made it up.

Having earlier said that I’m not a risk taker, I must admit I did eat a spaghetti Bolognese pizza back in a Kathmandu café when it was all over. By that time I had lost more than 10kg and figured my digestive tract must be bulletproof. It wasn’t.

You write about getting out into the deserts of the Red Centre for a ‘tonic of wildness’, and you’re not alone in this desire. Growing numbers of people are heading outdoors, undertaking hikes and reading books about walking. What do you ascribe this movement to?

I believe it’s a reaction to our modern world, the breakneck pace at which we live, the extraordinary demands this places on us. I am as guilty as anyone. But there is also a conversation humming along beneath the din of modernity, begging us all to slow down, find meaning, breathe. Smell the roses, if you like. It’s certainly like that for me, more than I would like, but, as you say, I don’t think it’s just me. There’s also the momentum generated by a good bit of representation; that we all now believe we need to walk and seek out wildness, because so many documentaries, movies and books are telling us so.

The nineteenth century American philosopher Henry David Thoreau found his answer in walking for at least four hours every day, or so he claimed. We don’t all get that chance, but maybe we should? In his journal, Thoreau wrote:

“I come home to my solitary woodland walk as the homesick go home. I thus dispose of the superfluous and see things as they are, grand and beautiful. I have told many that I walk every day about half the daylight, but I think they do not believe it. I wish to get the Concord, the Massachusetts, the America, out of my head and be sane a part of every day.”

I love the idea of getting the Massachusetts ‘out of my head’. His idea of wildness has been misconstrued as the more recent idea of wilderness, an area where nature rules and man’s influence is slight, sometimes defined as being of a specific geographic size. But while walking in nature is undoubtedly a fine practise, you can get relief from walking anywhere. It’s a lot to do with its rhythm, the repetitive pattern, the physicality of footfall. But walking in nature, or the wild, is certainly special somehow, and that's what has really grabbed our attention.

William Hazlitt believed the soul of a journey is ‘liberty, perfect liberty, to think, feel, do, just as one pleases.’ In an 1822 essay he writes: ‘Give me the clear blue sky over my head, and the green turf beneath my feet, a winding road before me, and three hours march to dinner.’ This sense of forgotten freedom looms large in our consciousness, a return to the garden, where ‘life was simpler’, and somehow we were ‘in tune with nature’. The urge is also fuelled by our reckless and cavalier attitude to environments across the globe, pressing issues like deforestation, climate change, fisheries management, plastics accumulation. We want a different future but feel powerless to make it happen against forces now global in scale.

Ideas of ambling and mindfulness—the latter has reached an extraordinary celebrity—are bound up with this lofty philosophical aim for walking, a return to the possible, where our thoughts can wander and we are as free to roam in our minds as we are along any path or across virgin countryside. It finds its expression in a return to ideas of pilgrimage and a re-embrace of spirituality: the Camino Trail and others, a reported upswing in numbers for the haaj, an increasing awareness of the close relationship between a walk and our intimacy with the places we live. In some way this all goes back to Thoreau, but of course he was not the first to express such notions. Walking as a cultural practice was very popular from the late 18th century on. And not everyone liked Thoreau of course; Robert Louis Stevenson apparently thought him ‘a skulker.’

Which of the walks in the book would you recommend to people who want to explore Central Australia for the first time?

There are several, but I’m thinking to cater to different levels of mobility. Many of my walks start at my back fence where I just head off into the hills. One of the easiest to do, however, is one I do quite often to clear my head and I use it as a writers walk at the biennial Alice Springs Writers Festival.

It is readily accessible, and about 4km distance from the Alice Springs Telegraph Station (north of town) along the shady banks of the Todd River south to the Alice Springs CBD. In the epilogue of Songlines and Fault Lines I take a detour from this route and walk up Anzac Hill to watch the sun rise.

Recently the trail was concreted, which hasn’t been a bad thing as plenty of cyclists and parents pushing strollers can now share the experience. On a sunny winter’s day in the Centre, the temperature might rise from zero in the early morning to the early twenties by midday, and so there’s nothing more pleasant. At one end is the history of the famous Overland Telegraph Line (and the lesser known role of the Telegraph Station in housing Aboriginal children of the stolen generation), and at the other you can stop for a coffee and brunch at one of the great cafes in the town. The detour up Anzac Hill to oversee the town is an easy enough climb if you take it steady; you can take the road or there is a stepped path from the town side. A great place to get your bearings.

Another place I talk about in the chapter on Bruce Chatwin is Olive Pink Botanical Gardens; it’s quite beautiful, an arid zone flora reserve founded by anthropologist and activist Olive Pink in 1956. This is more an amble around than a hike from A to B. And there’s a very salubrious cafe, as well as the amazing sense of achievement of Olive Pink, who lived at the site in a tent and lobbied the government to declare it a reserve.

The chapter on Arthur Groom starts with my wife Fiona and I walking to Wallaby Gap along Section One of the Larapinta Trail. It’s a stunning walk, one of the easier sections and close to town. The through walk to Simpsons Gap is about 23 kilometres and easily achievable as a day walk for the reasonably fit. But you'll need a lift back. The route takes in some stunning views of the West MacDonnell Ranges, and looking back to Alice Springs.

There are so many other sections of the Larapinta Trail and beyond, as well as the Centre's spectacular gorges where you can swim if the weather is warm. I’d advise anyone thinking of this to contact NT Parks and Wildlife or go to their website in the first instance.

You mention that you wanted to tackle the pervasive perception of Central Australia as a frontier or an empty wilderness. What prompted this urge, and how have you sought to address such views in the book?

The book tries to find ways for the various histories of our country to knit together, to better inform each other. Many call Alice Springs and Central Australia the frontier, the supposed divide between black and white, primitive and modern. Actually, the historian Richard Davis calls the frontier ‘one of the most pervasive, evocative tropes underlying the production of national identity in Australia’. As with many popular notions, however, it’s more complicated than that. In the press Alice Springs is a town divided, a violent dysfunctional mess of racists and drunken Aboriginal people. But it is in fact a much more sophisticated and integrated community than a frontier, where there is a clear divide between us.

I had wanted to write some of the good stories of Alice Springs as a counterbalance to all the bad. People’s perceptions of the Centre hinge on perceived differences between Aboriginal and settler Australians. And really, this forms the bulk of the discussion around race relations in Australia, our differences. But there is so much the same too… one example from the Aboriginal people I know is their sense of humour: we always seem to be laughing. Sure there are things we differ markedly on. But love, pain, caring for family, fresh air and country, all these things we share. It occurred to me that by comparing stories of walking across cultures, we might compare the ways of being and perceptions of landscape that we share, rather than always talking about what divides us. I started to think the idea of frontier might be self-fulfilling, that continuing to imagine it this way was preventing us from reimagining the place as home. And so this a layered compilation of stories of walking the Centre emerged, to explain the many ways we all think about it. I wanted to give something of the lived experience of the Centre, some of the joy it brings, as well as not squib on its many challenges.

How do you think the idea of wilderness has changed since the days of Arthur Groom’s representation of it in I Saw a Strange Land?

I would hope we are coming to more nuanced ideas of the notion of wilderness, that don’t necessarily preclude humans and at least acknowledge their influence. Groom saw the Centre as a sort of ‘museum piece’, a place and a people that needed preserving for future generations. In one sense I’m glad he did, for there are big national parks here now. But we also needed to develop a more sophisticated perception of Aboriginal people, who had long been here and had to a significant extent shaped the landscape to their own needs. Any idea of such a land as ‘untouched’ is obviously misleading. Grooms’ view of Aboriginal people as a primitive race doomed to extinction, one needing to be ‘preserved’, runs counter to the evidence of a culture that was dynamic, and that managed to survive a forbidding environment through ice ages and other cataclysmic change. True, in some locations areas of particular value were ‘museumed’ by Aboriginal people themselves, not burned or hunted, so as to preserve particular species or environs. But the wilderness viewpoint where only a ‘primitive’ Aboriginal people might dwell, was hampering those who embrace the modern world and want full-time work and jobs for their children.

The latest research from the Top End, published in July in Nature, pushes back the length of time Aboriginal people have walked the Australian continent to about 65,000 years. The Australian landscape is no wilderness, it is a landscape shaped by cultural practices. But this also doesn’t mean giving up our ideas of walking in country where the apparent presence of man is slight. There are fewer and fewer places where this is possible, and the rate at which we are losing or destroying them is a human-led tragedy. Australia is still a staggeringly beautiful country, and its Aboriginal history only adds a further layering to that beauty.

An outsider himself, how did Bruce Chatwin’s The Songlines challenge and transform existing understandings of Aboriginal Australians’ existence and walking in Central Australia?

The songlines resurface in Chatwin’s book after being lost under ideas of Australia that were expounded in earlier literature, as a ‘land of opportunity’, as ‘wilderness’, or the place where nomadic Aboriginal people might go ‘walkabout’ at any moment. I think you either love or hate the book; there’s not much in between… I happen to love it.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of The Songlines, which arrived in 1987 as Australians were already changing their attitudes to Aboriginal culture. This was the Land Rights era, where Aboriginal people started to regain rights to their own country under Australian law. It was also the ‘hippy’ era, and to an extent the book became a symbol of this free-wheeling generation; Chatwins’ themes helped to evoke travel as something that linked us back to the savannah of Africa, to our biological roots, and gave meaning to our existence.

I think Chatwin understood well that the Aboriginal story was crucial to any ‘Australian’ story, as well as (more cynically) being a terrific hook on which to hang his ideas of nomadism as cure for an ailing West. Nonetheless, The Songlines reminded us that Australia is a living landscape for Aboriginal people. This is evidenced in the fact that the songlines are increasingly travelled, although these days mostly by car rather than walked. There is also a curious similarity between our modern travel networks and the ancient walking routes that cross the same landscape. Many explorers followed the Aboriginal Dreaming tracks, led directly by Aboriginal people, or, as in the case of John MacDouall Stuart, indirectly by an Aboriginal presence, and which he came to realise marked the likely location of water.

In contesting the pejorative term ‘walkabout’, you suggest Aboriginal walkers are better described as undertaking a form of pilgrimage. How did you go about researching Indigenous conceptions of Central Australia, and did you face any particular challenges along the way?

The original research for the book was undertaken as part of PhD at Macquarie University, and later published by MUP as an academic monograph called Writing Home. My idea was to use walking as a point of commonality or intersection between Aboriginal and settler Australian cultures, in order to compare the ways we think about and perceive the places we live. A pilgrimage is a life changing event, it has a certain route that is of spiritual or secular significance, and an expected outcome, a change in the pilgrim. Aboriginal stories from the Dreaming Tracks echo this practice familiar from Eastern and Western traditions, but it is not how we usually think of the Aboriginal tradition. And yes the similarities are unmistakeable. ‘Walkabout’ is how we think of these traditions, still widely used to dismiss Aboriginal cultural practice, and only serving to present Aboriginal practices as mysterious and inexplicable, further reinforcing any divide between us. By viewing Dreaming stories and the walking (or travelling) of the songlines as a form of pilgrimage, which it resembles in so many ways, it gives whitefella Australians a peg on which to hang a better or more nuanced understanding of the songlines. Walkabout emerges as a much more serious business, of economics and trade, of marriage and emerging adulthood, of song and storytelling and celebration, of nationhood and survival.

I was already talking to a lot of Aboriginal people as part of my work here as a journalist, and even more so as part of some work in community engagement on the town camps during the SIHIP redevelopment project from 2010. And simply living in Alice Springs means you begin to absorb elements of the ongoing and always pervasive cross-cultural conversation as part of your day to day life, what Robyn Davidson refers to as ‘The Conversation’. My background was in geography, so there was an established interest in ideas of landscape and humans’ relationship with it. Therefore I decided to use my research time to read deeply of the anthropology and political background, combined with walking the landscape myself, to start to unpack the very complex social situation of the Centre. Nonetheless, I also sought counsel from a lot of people: Aboriginal traditional owners, anthropologists, historians, geographers, other writers. Then I brought all of these accumulated ideas to the walking literature of the Centre—a literature which is hugely extensive, by the way—and which articulates individual snapshots of a variety of lived experiences of the landscape. By examining walking stories from across the history of the Centre since precolonial times, it was possible to construct a makeshift timeline of changing popular perceptions of the place.

As for challenges, I was constantly aware of the identity politics that pervades this space, of whom should speak for place. It is increasingly clear that Aboriginal people have and should have their own voice in articulating the Australian landscape, that whites need not speak on their behalf. In fact the Aboriginal oral storytelling tradition is a form of literature in its own right, one comparable to the great storytelling traditions of history. That Aboriginal languages and the stories that go with them are being lost is a tragedy beyond compare.

And Aboriginal people certainly have every right to be angry over what has happened to them under colonialism. But when it comes to writing about the places where both cultures now dwell, the picture is not so clear, it becomes a much more complicated and vexed question. Any approach to writing place has to be multi-layered and respectful of the other members of the conversation. In speaking about Alice Springs, one cannot speak about the place without embracing all the various cultures and their histories. To do so would give a very hollow portrait of a place. And this is as true for Aboriginal as settler writers. More and more stories from Aboriginal authors adorn our bookshelves, and this is very exciting. But there should be no problem for a writer of any culture accessing this fabulously interesting material and enhancing their knowledge of Australian places. Songlines and Fault Lines calls for a more mature conversation about cross-cultural spaces, one where everyone’s voice is respected, and everyone has a right to be heard.

Finally, Alice Springs has a varied and, to an extent, transient population. Many people stay a few years before continuing on, complementing the town’s already diverse makeup of white, Aboriginal, immigrant and itinerant inhabitants. How do you think this mix of different people influences ideas of home and belonging in the Red Centre?

More than three thousand Indian people now live in Alice Springs, alongside a considerable number of African refugees, Italians, Greeks, Aboriginal people, and other Australians. The early development of the Centre gained momentum thanks to the German Lutherans, who established the Hermannsburg mission and other sites, and whose descendants still thrive here. There are the Afghans, whose skills with camels shaped early transportation routes before the rail came to Alice Springs in 1929. Many groups boast mixed heritage as well as Aboriginal descent.

Home for any human being is the place you feel safe and secure, a place where you properly belong. This becomes problematic, however, when you consider the recently arrived refugee or immigrant who has built a long-standing relationship with another place, their original home. I was born in Australia to an American father and third generation English mother. Of course, settler Australians are all immigrants to more or less an extent, but it doesn’t mean they have any less of an urge to make a home to live in.

David Malouf talks of Man as ‘Man the Maker’, one who shapes the landscape for self and family. My approach was to use this as a way to look between the cultures for the humanist roots of our ideas of home, the common elements that cut across culture. The philosopher Gaston Bachelard refers to a ‘nest’, how an invertebrate that likes to withdraw into its shell. I liked this idea. While our individual shells may differ in form and nature, the impulse remains. We’ve all had that feeling of shutting the door to the world outside, of ‘being home’.

For myself, I felt a bodily sense of home when I arrived in the Centre in 1998. But home is also the stories we tell ourselves, the social relationships we develop and the importance we assign to the places around us. It is the memories and events invested in particular locations. Think of the pencil marks on a wall of the successive heights of our children as they grew; the room where everyone was last together as a family; that special spot where you feel most at peace. All of these conjure a sense of place, the being-ness of our lives, the idea of home.

Songlines and Fault Lines is out now.