EXTRACT: Barbara Tucker and Heide

Lesley Harding and Kirsty Grant remember Barbara Tucker's contribution to Heide Museum of Modern Art.

In the late 1990s Barbara and Albert Tucker made the magnanimous and bold decision to donate a significant proportion of their personal collection to the nation. While this generous gesture included a select number of gifts to state institutions and the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra, they determined to transfer the major part of the collection to Heide Museum of Modern Art in their hometown of Melbourne. It was the culmination of a decade of deliberation, discussions with the Victorian Government and a series of false starts. The Tuckers had preserved a strong and representative group of paintings and related material spanning the depth and breadth of Bert’s career and they felt it was ‘vitally important’ that these works stay together and be made available for public viewing.

The Albert and Barbara Tucker Gift, on long-term loan to Heide from 2000 and progressively donated since 2005, was to the Tuckers’ thinking a fitting acknowledgement of the role John and Sunday Reed had played in Bert’s nascent career. As Barbara related, he had ‘a sense that the proper destination had been reached ... that the body of work would be housed in a place inextricably involved with that surge of creative energy of which in his youth he had been so much a part’. Bert was one of a number of artists in Melbourne who received the Reeds’ encouragement and support in the late 1930s and 1940s, and benefited richly from the stimulating environment and congregation of like-minded people at their property near Heidelberg. The Heide years had been for him a period of great personal development and creative growth, and though there were times of conflict, turmoil and even heartbreak, Heide was a place where a life in art was made possible. With this gift the museum would be the recipient of nearly two hundred artworks. ‘I’m very pleased,’ he told his biographer Janine Burke. ‘I’ve done the right thing. My works have gone to the right place.’

Along with paintings and drawings by Albert Tucker dating from 1938 to 1995, the Tucker Gift also represents his close colleagues Yosl Bergner, Arthur Boyd, Joy Hester, Sidney Nolan and Danila Vassilieff. Collectively these artists had begun their maturation during the Depression and had nothing to lose by taking artistic risks and committing to avant-gardism. As Robert Hughes pointed out from the relative proximity of the 1960s, ‘Commitment returned to painting; such vitality in a group had not been seen since the Heidelberg school’. They staged ‘not merely an aesthetic revolt, but a revolt of ideas’.

At a time when Bert and artists in his milieu found their work commercially and critically at odds with convention and public taste, the Reeds’ openness and generosity was, if not essential, then at the very least affirming and sustaining. While Nolan had his own arrangements, living at Heide on and off for seven years during the 1940s, Bert and his first wife Joy Hester received practical assistance from John and Sunday by way of a weekly stipend—just enough to keep the wolf from the door during the privations of World War II. For Bert this assistance continued for more than a decade, until 1953. This was not mistaken by either party as charity, but neither was it loaded with tacit expectation—‘I never had to sing for my supper,’ Bert said. He wrote articles and edited the Sociological section of the Reed-financed Angry Penguins journal during the mid-1940s as one way of earning his living.

The Reeds also purchased his art at a time when there were few buyers, though in truth their investment was much more than financial. They believed in the ambitions and aesthetic and intellectual challenges Bert and his peers had set themselves. As John Reed described, ‘Prior to 1938–39 the whole atmosphere was one of stagnation and death, and to be able to share in the activity which so utterly and irreversibly changed this situation, was a truly beautiful and exciting experience.’

After living overseas between 1948 and 1960, Bert came back to Melbourne. It was a triumphant homecoming; having left Australia as a self-described ‘refugee’ from his own culture, he returned with new perspectives and accomplishments. John Reed, by now the director of the Museum of Modern Art of Australia, arranged both an exhibition and a bursary to support Bert’s return. The exhibition toured nationally in 1960–61 and at its close Bert was able to use the proceeds from sales to purchase outright a 3-acre property in Haleys Gully Road, Hurstbridge. After marrying Barbara in 1964 he entered a productive and settled phase of his life. For the best part of the next twenty years he painted almost exclusively the raw, untempered landscape of his immediate surroundings, populating his images with fauns from classical mythology or the darting, sometimes menacing parrots of the Hurstbridge environment. Barbara purchased indigenous plants from the Forestry Commission for the garden and turned her green thumb to growing vegetables, while the rest of the property was preserved in its natural state. She later talked fondly of their immersion in that locale—not far from Heide—drawing strength and inspiration from their walks in the bush nearby, and how during this time Bert helped her to ‘see’. Writing for a Heide exhibition catalogue in 2008, Barbara explained that he forever changed the way she viewed the natural world, describing it as ‘the greatest gift one person can give another’.

Although Barbara had met the Reeds on several occasions and visited Heide a number of times, she knew them best from Bert’s incisive stories. While he was grateful for John and Sunday’s early support, his relationship with them was as complex as it was longstanding, especially after the Reeds formally adopted Sweeney, his and Joy Hester’s son, in 1953. It was a binding, painful and emotionally fraught situation and when Barbara talked with us about it—knowing she could not speak for Bert but wanting to uphold his version of events—she remained loyal and consistent in her accounts, wanting the facts to prevail but with the proviso that the handling was sensitive.

The milestones and achievements of Bert’s career were much easier to speak to, and so she did enthusiastically and sincerely. Many of these have been explored and celebrated in Heide’s ongoing program of exhibitions over the past ten years in the Albert & Barbara Tucker Gallery, the cornerstone of the museum’s 2005–06 redevelopment and purpose-built in acknowledgement of the Tucker Gift. Barbara was unflagging in her support of the program and the research that accompanied it, ever patient with the curators’ myriad and sometimes obscure enquiries. She made everything in her own collection available for loan—even if that meant rehanging her living room—and was warmly generous with her guidance, encouragement and bottomless cups of tea.

Alongside his paintings, Bert’s photographs hold a special place at Heide; they are the aperçu through which we have come to know the people associated with its rich heritage, particularly the vibrant years of the 1940s. Although the Reeds have since been duly recognised for making their indelible mark on Australian cultural history, it is largely through Bert’s intimate, unposed photographs that John, Sunday, Heide, their friends and associates and the remarkable stories of their lives and times have a contemporary visibility and familiarity.

A selection of Bert’s photographs from the 1940s and beyond were enlarged as exhibition prints for the hugely successful Eye of the Beholder exhibition that toured Australia in 1998–2000 and for a related show at Lauraine Diggins Fine Art in Melbourne. Barbara subsequently donated more than a hundred of these editioned photographs to Heide in 2001, including some beautiful portraits Bert took of her at Hurstbridge and Springbrook and a number of more spontaneous images of her with friends.

Fully understanding the cultural value of the material, in 2008 Barbara donated the original contact prints—then still housed in an old cigar box—together with many hundreds of photographs and negatives in her possession jointly to Heide Museum of Modern Art and State Library Victoria. To her thinking this was an ideal solution: the curators at Heide would be able to work with, exhibit and publish the photographs freely, while the library had the capacity to preserve the original material in cold storage and digitise the images, making them available to the wider public.

Barbara’s magnanimity continued in 2011 with the gift to Heide of a substantial visual and literary archive comprising Bert’s sketchbooks, early paintings and drawings, manuscripts for articles and lectures, photographs, press clippings and catalogues, together with some of his and Barbara’s fascinating library of books. The archive has, needless to say, been essential to the generation of new scholarship on the art of Albert Tucker and the wider group of artists associated with Heide. But for Barbara there was a further, more personal motivation for her largesse, which extended over many years:

The gift of Tucker’s works and those of his friends, is not only a matter of these important art works finding their natural home. The gift should be seen as the completion of a circle in human affairs. It is Bert’s, and my, heartfelt gesture for the healing of wounded relationships within that circle. It is a gesture intended to reconcile the estranged spirits of John Reed, Sunday Reed, Albert Tucker, Joy Hester and Sweeney. It is a gesture that demonstrates Bert’s personal resolution of, and ease with, that historical moment in his long and immensely productive life.

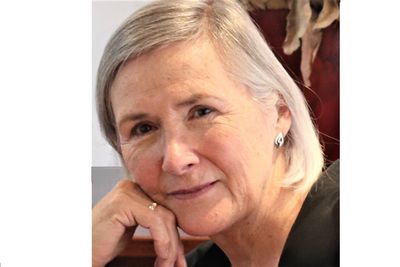

These donations are an apposite tribute to Albert Tucker, who thought that the past was always omnipresent, but they also speak volumes about Barbara. An important member of the Heide family, Barbara’s legacy will live on at the museum— through the Gift that continues to be shared with visitors, and through the friendships she established with Heide staff, past and present. The walnut tree that was planted in the Heide gardens in her memory in 2015 stands as a permanent and personal reminder of Barbara, her love of the natural world, and her great support of all the museum’s activities.

This is an extract from Barbara Tucker: The Art of Being, edited by Hermina Burns, publishing 20 February 2024 with The Miegunyah Press.