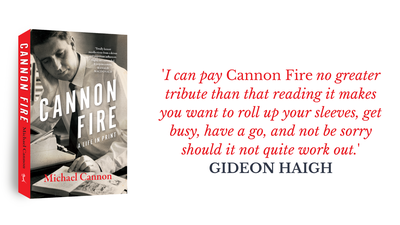

Gideon Haigh launches Cannon Fire: A Life in Print

Lord Northcliffe said that the true journalist was interested in everything but themselves. It is a view very much out of fashion. In modern journalism, stories are increasingly a means of self-advancement, to the extent of journalists turning into memoirists, fascinated by their reactions to things, and expecting us to share that fascination. ‘Reader,’ I saw a recent TV review begin. ‘When I watched this series, I wept.’ The humanity!

Then there’s the popular game: where’s Walkley? The decline in the quality of journalism is inverse to the growth in awards. Are they related? I couldn’t possibly comment. But journalism reminds me increasingly of a South American junta where the generalissimos spend most of their time pinning medals on one another.

So to this cameo of Michael Cannon. It's a memoir, too, though undisguised, and at the end of a long and storied career. Michael's books have sat proudly on my shelves for years, but I had no solid idea of their provenance until Nathan sent me Cannon Fire. It is a little classic of journalism in its raffish, rough-edged, pork-pie-hatted avatar; it is unusual, too, in not being concerned with big city newsrooms and screaming cries of ‘extra, extra’. Michael might have descended from Monty Grover, but he went his own way in journalism: reporter, columnist, editor, printer, proprietor, gadfly. Michael was self-deprecating about his skills: ‘As a journalist supposedly attuned to public tastes, I was pretty much a failure.’ He jibbed at the tyranny of the inverted pyramid, which he observed was at odds with principles of storytelling ‘where the writer must slowly build up to a crisis’. He personified instead the independent media avant la lettre. Cannon Fire is replete with superseded and forgotten mastheads and titles: we might call them start-ups these days, but they glow in hindsight with high spirits and optimistic forecasts. He reminds me of a favourite line by Claude Cockburn which has always resonated with me: ‘An editor has no business publishing what the public wants. He should be publishing what he wants and convincing the public to share his interest.’ That the editor might occasionally fail to locate that G-spot of reader excitation is no justification for not trying.

Michael was also a self-described generalist – a classification regarded with suspicion in this increasingly professionalising and specialising age. He was game for anything. When Cyril Pearl lent him a precious copy of George Meudell’s The Pleasant Career of a Spendthrift, it sent him skipping along the path to the 1890s, and The Landboomers, still a landmark work of history that he tackled by intuition not training. Was he a journalist? Was he a historian? Of course, he combined both: he saw the bones of history poking through current events, saw the journalistic potential in a good story whatever its antiquity, and considered qualifications secondary to curiosity. As almost certainly the least educated person in this room, I’m totally with him on this.

On the spectrum of memoirists, Michael would probably be grouped at the personally circumspect end. There is no whiff of gunpowder in Cannon Fire, which is cool, seasoned, and foregrounds the work of years. The exception, perhaps, is the tenderness of the portrait of his father Arthur, with whom I suspect Michael privately identified. There is a telling exchange early on: ‘My father gave me some parting advice before he went to the RAAF training camp. “Never be beholden to anyone,” he told me gravely. This meant, he said, that you should never accept favours or assistance from anyone if you could possibly avoid it. In other words you had to learn to stand on your own feet. This was the longest talk I ever had with him. Aged eleven, I would mull over his words and eventually agree that they formed a sensible philosophy of life.’ It explains a good deal about his resolute autonomy as a writer and publisher; perhaps also his late life realisation that in concentrating so hard on his work he had failed to perform the emotional labour on which a family depends.

Cannon Fire instead reeks of ink and ingenuity, that so-rare combination in Australia, and this country's tradition of auto-didacticism, never scarcer. There's an old joke about the Australian who's asked whether he can play the violin. 'I don't know,' he replies. 'I've never tried.' I can pay Cannon Fire no greater tribute than that reading it makes you want to roll up your sleeves, get busy, have a go, and not be sorry should it not quite work out.

Still, I’m delighted that he was able in Cannon Fire to produce this small but perfectly formed capstone on a thoroughly idiosyncratic and fruitful career. I'm delighted too that MUP should have published this small but perfectly-formed capstone on a thoroughly idiosyncratic and fruitful career.