Frank Bongiorno's speech launching Phillip Deery's Spies and Sparrows

Frank Bongiorno's speech launching Phillip Deery's Spies and Sparrows

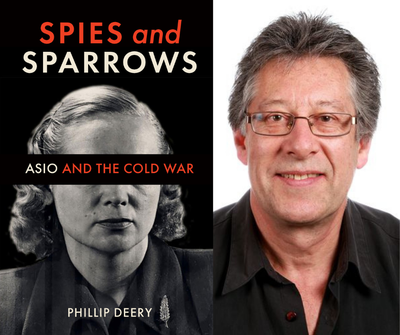

Spies and Sparrows: ASIO and the Cold War by Phillip Deery

(Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 2022)

Frank Bongiorno (The Australian National University)

Launch Speech, Readings, Carlton, 8 March 2022

I begin by paying my respects to the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin nation on whose country we meet tonight.

We’re privileged to have Phillip Deery’s Spies and Sparrows: ASIO and the Cold War for several reasons.

In the first place, it’s the work of Australia’s leading cold war historian. Phillip’s knowledge of the primary sources, of the historical scholarship, of the key personalities, living and dead, is incomparable. His own contribution to our understanding of Australia’s cold war has been formidable: through a vast body of published scholarship, through memorable performances at conferences, through his teaching and supervision, and, increasingly in recent years, through his book reviewing in the weekend papers and his voice on the airwaves.

He is also, quintessentially, a post-cold war historian. While Phillip has been working on aspects of the cold war much of his career, going back to his ground-breaking research in the coal strike of 1949, his approach to cold war history had been shaped by the rich documentary record that has become available internationally since the 1980s. The availability of the Venona decryptions from the mid-1990s is perhaps the best known of these breakthroughs, allowing historians themselves to decode a past that had previously been more resistant to their attentions. Then there are ASIO files, especially the famous – or infamous – Series 6119. Even a cursory glance at the endnotes of Spies and Sparrows reveals multi-archival, multi-national research of a kind that has become possible, although by no means easy, with the end of the cold war itself.

There is more to it than that: Phillip is a global cold war historian. His previous book, the splendid Red Apple, was on Communism and McCarthyism in New York.1 His latest is on Australia, but at every point I was conscious, as a reader, of being told about an Australian aspect of a large and important global story. Global histories of the cold war usually have little to say about Australia, as I discovered while teaching with Odd Arne Westad’s book on that subject.2 But Phillip has an outstanding international reputation as a cold war historian, as well as a superb grasp of the Australian story. We are in expert hands as he guides us through both the global and the local aspects of the subject.

Phillip is also a marvellous storyteller. Those of us who know Phillip, know this well already. Many more are discovering his gifts in the media, and in Spies and Sparrows. Whether he’s telling us a joke over a drink – and you can see him in action telling me one in a photo on Facebook at the moment of the punchline – or narrating the tragedy of lives blighted and careers damaged by ASIO’s war on domestic subversion, we hang on Phillip’s every word.

Phillip is also a humane historian. It is perhaps unsurprising that he is so attracted to biography as a way of exploring cold war history because his fundamental interest is that of a social historian: how did the cold war shape the lives of ordinary people? He did this movingly in Red Apple. He has done it again here, and superbly again. In Spies and Sparrows, he tells his story through eight lives. There are, of course, many other lives in the book – familiar names such as Chifley, Menzies and Spry, among others. But his eight are well chosen.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

1 Phillip Deery, Red Apple: Communism and McCarthyism in Cold War New York, Empire State Editions, an

imprint of Fordham University Press, New York, 2014.

2 Odd Arne Westad, The Cold War: A World History, Penguin Books, London, 2017.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

There is Tom Kaiser, the brilliant young scientist who paid a heavy price for his decision to join a protest outside Australia House in London against the Chifley Government’s strikebreaking during the coal strike: Kaiser lost his job with CSIRO. Phillip is brilliant in explaining the intersection of the world of high politics, diplomacy and intelligence with the lives of people such as Kaiser. In this case, Kaiser’s misfortune was that his protest came at a time when the Chifley Labor Government was seeking a reversal of an embargo that the United States had imposed on passing intelligence to Australia because of concerns about the security of institutions such as CSIRO. In the end, Kaiser paid a smaller price than many for his entanglement in the paranoia of the cold war. He would go on to a highly successful career as a physicist at the University of Sheffield. Britain’s gain was Australia’s loss.

I need to be careful in not giving away too much of Phillip’s story: at the launch of a murder mystery, no one wants to be told that the butler did it or, as Malcolm Turnbull put it recently, ‘It was Colonel Mustard in the library with a smartphone’. Some of you will have read Phillip on the infamous William ‘Diver’ Dobson, or possibly heard him talk about this remarkable tale on the radio. But I can say this much: Dobson doesn’t conform to my image of a typical member of the ALP’s anti-communist Industrial Groups of the 1940s and 1950s; rather, he seems more like some of our better-known conmen or tricksters, such as John Friedrich, of 1980s National Safety Council of Victoria fame, or Peter Foster with his slimming tea and other scams too numerous to mention, or any number of State Liberal MPs in Victoria. One of my favourite moments in this book, however, was when Dobson managed to gain an appointment teaching industrial relations in the economics department at Melbourne University in the early 1980s. To be fair, as a veteran of the industrial struggles of the cold war, he might these days qualify to be appointed a ‘Professor of Practice’.

Dr Paul James’s ‘crime’, in May 1950, was to have seconded a motion objecting to the Communist Party Dissolution Act and asking the ACTU to consider a 24-hour stoppage at a meeting of the Hospital Employees’ Federation in Trades Hall. He therefore had to be sacked from the Heidelberg Repat. He also had his home raided by ASIO officers looking for evidence of Communist Party membership, and his briefcase stolen by ASIO during a Peace Conference. If you want a hint of what an Australian police state might have looked like had the Coalition government got its way in 1950-51 over the banning of the Communist Party, read Phillip’s chapter on Paul James. It is in James’s story that we can most clearly see that the target of the Menzies Government and its spies was not so much subversion as political dissent.

We also have the stories of two remarkable women. There is Anne Neill, an Adelaide widow, but also an ASIO sparrow infiltrated into the Communist Party branch in South Australia. Comrade Anne begins chapter 4 making pickles and marmalades for the Party and ends it an anti-Semite in the orbit of Eric Butler’s rancid League of Rights. In the meantime, she was a valuable asset to ASIO, passing on bucket-loads of information to them about the Adelaide comrades. They also thought the world of her, until they began to ask questions about how a poor widow was able to pay her own way to a World Peace Congress meeting in Moscow, described by Phillip as her ‘crowning success’ as an ASIO agent. No doubt we can thank Anne for the absence of any revolutionary outbreak in Tom Playford’s South Australia which, it should be recalled, Australia’s delegate to the conference of the Second International in Stuttgart back in 1907 said would indeed be the place where world revolution was destined to begin. Lenin was there that day.

Phillip then moves on to Evdokia Petrov. She has long been part of the story of the Petrov defection, but most commonly as the woman who lost her shoe. She figures as media image. She figures as wife. Phillip shows that she was an important operative in her own right, possibly with more potential for western intelligence as a defector than her husband Vladimir, whose drunken escapades Phillip narrates in a rollicking black comedy. But Phillip also reveals the domestic misery and personal tragedy behind the public history of the Petrov affair. ‘A Strindbergian gloom prevails’, one spy’s report declared of the Petrov home in 1957. Could this be a deft, witty, apposite literary reference by an ASIO officer, you might wonder? No, of course not: it was an MI5 security liaison officer’s report. The Petrovs never felt safe from the hand of the KGB assassin, but Phillip’s analysis of the psychological costs of defection is as subtle as his handling of the experiences of the ASIO plants who appear in other chapters.

In the chapter on British serviceman Michael Brown, Phillip is in his element in examining the intersection of personal biography and high politics: in this instance, Australia’s interest in acquiring nuclear weapons is jeopardised by Brown’s sale of top-secret documents about the missile tests at Woomera. With Demetrius Anastassiou, we meet a Greek immigrant whom ASIO wanted to prevent from returning to Australia after attending the Berlin Youth Festival. The country’s customs and immigration system was too inefficient actually to prevent his return, so the government was then faced with the problem of how to deport him. ASIO was all for kicking Anastassiou out, Immigration was opposed. The government eventually decided that migrants should not be deported in this way, evidence, perhaps, of a residual liberalism in an age of repression. That liberalism has been well and truly eradicated from our own age of repression.

The final chapter, on Maximilian Wechsler, tells the tangled story of a Czech refugee whom ASIO would use to infiltrate several left-wing organisations during the Whitlam era, a period in which its own activities came under an unprecedented scrutiny. Again, I don’t want to give anything much away, as the chapter contains a remarkable story of a descent into the bizarre and baroque. Perhaps the image that best sums up our man is of his doing an interview on the television program, A Current Affair, in March 1975 with his semi-automatic rifle lying at his side. This was the man whom the Liberal Party’s deputy leader in the Senate, Ivor Greenwood, considered would be a useful ally in undermining the security credentials of the Whitlam Government. It was quite a time, the 1970s.

Phillip writes with empathy, compassion and understanding, not only of those with whom readers might identify and sympathise but with others whose lives were shadowed by their own deception and betrayal. He is sensitive to the psychological gains and losses involved in passing oneself off as a communist while being an ASIO plant. None of this can have been easy as historical writing: several of the people who figure here will command the admiration of very few of us, yet Phillip always takes them seriously and treats them respectfully as historical actors. Manning Clark would have called this ‘the eye of pity’ which, he believed, we owed to all of those we encounter in our work as historians – even Robespierre, he thought, as hard as that was.

Phillip might not call it such, but he, too, has ‘the eye of pity’. He also has a sense of humour. There are plenty of laughs along the way, but the pervasive sense is of futility, even of tragedy. ASIO generated a large, self-perpetuating bureaucracy that confused dissent with subversion and political commitment with espionage, and treated as a threat to social order a party that was, throughout the cold war, in terminal decline and prone to fragmentation. It began countering espionage but soon degenerated into a kind of police force invigilating those deemed disloyal because of their political beliefs. That image with which the book begins, of Phil Geri, a Bendigo hospitality orderly, still spying on a local branch of the Communist Party (Marxist-Leninist) in the 1980s, after 23 years of working as an ASIO mole, is a study in pointlessness. His assignment with the Maoists had only come after the Communist Party branch in Bendigo had dwindled to three members and his surveillance there was no longer felt to be needed.

It was the Stalinist USSR or even McCarthyist America, but the costs – to the trust that democracy needs to thrive, and to the individuals whose lives become entangled in ASIO’s net – were far from negligible. Phillip is skilled in capturing the past’s otherness but he also writes with an eye on the present. The power of the security services in Australia has grown massively in recent years and poses a menace to individual rights, as it did in the cold war, even if it is no longer so obviously the instrument of one side of politics – as it became in the Menzies era. Phillip, then, has produced the very best kind of history: one that discloses dark and difficult aspects of our past while speaking to the pressing dilemmas of our present. I have much pleasure in declaring Spies and Sparrows: ASIO and the Cold War duly launched.