Ghosts but not golf at the Abbotsford Convent

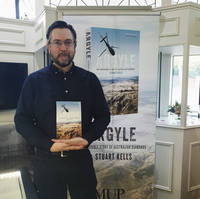

The Abbotsford Convent was this haunted place, left to languish for years after the last of the Sisters of the Good Shepherd had gone. In its prime it had been a school, a refuge, a retreat, a workhouse and a prison - the single largest charitable institution in the southern hemisphere. In the late 1990s a proposed high-density development threatened the idyllic riverside location, sparking outrage in the local community and further afield. Years of protesting, negotiating and fundraising followed and the convent, now on Australia's National Heritage List, has started a new life as a vibrant centre for art and culture. In this piece, historian Stuart Kells offers a glimpse into his latest work, The Convent.

Today, the Abbotsford Convent occupies most of the Abbotsford peninsula, a heart-shaped site formed by a sweeping bend in the Yarra river. Ordinarily (in non-covid-19 times) it is a popular destination for visitors from near and far. The place has a unique atmosphere and a strange energy – perhaps because it is populated with an overabundance of ghosts.

In the 1840s, European colonists swept away traces of tens of thousands of years of Indigenous ownership and land use on the site. The colonists converted the culturally important peninsula into picturesque ‘farmlets’, which served as fashionable homes for the successful merchants, judges and MPs who led the new colony.

Then, in the 1860s, two of the colonists’ fine homesteads – Abbotsford House and St Heliers – formed the nucleus of an ambitious religious mission. The goldrush had torn Melbourne’s social fabric. Many women and children needed help, but most charities welcomed only the ‘deserving poor’. Nuns from an obscure French order, the Sisters of the Order of the Good Shepherd, had a more inclusive ethos. In Melbourne they would provide a retreat and refuge for so-called ‘fallen women’.

From this beginning, the Abbotsford Convent grew to become a crucial Melbourne institution, and one of the largest charitable foundations in the southern hemisphere. The Sisters commissioned handsome buildings, largely in the Gothic style. The convent was a godsend for many of its residents, though far from all.

The Sisters had been influenced by the nineteenth-century doctrine of ‘contamination’. The fear was that social ills could pass virally from one group to another through contact. So the convent’s residents were assiduously categorised and quarantined from each other.

The separation was maintained even during worship. The convent’s main church is notable for the partitioning of its interior to accommodate different categories of residents and inmates, so they could attend the same services without interacting. For many women and girls, the convent was like a prison, the nuns its cold and distant warders.

In the 1960s and 70s, after Vatican II, the Order adopted a less rigid rule and a more progressive approach to care and outreach. Most of the convent was closed, most of its land sold. It became for a time a college campus, but by the late 1990s the site was largely derelict. A private developer made plans to reshape the old convent into an exclusive residential enclave. Vaunted features of the redevelopment included apartment towers and a ‘chip-and-putt’ mini-golf course.

When nearby residents learned of the developer’s vision for the site, they began a campaign to protect the convent's buildings and grounds, and to establish a community-owned arts and cultural precinct.

At the time, there was little high-rise development along the Yarra outside the CBD. Large areas of nearby land were vacant and underdeveloped. Today, however, accessible open space is at a premium, the Yarra is at risk of encroachment and overshadowing like never before, and the density of suburbs such as Richmond and Abbotsford has skyrocketed. In retrospect, the decision to protect the convent site from intensive redevelopment looks extremely prescient.

Possums, kangaroos, wallabies and quolls had disturbed the nuns’ first nights on the Abbotsford peninsula. Now, descendants of some of those fauna still live on and around the peninsula: bluetongues, possums, the occasional snake and, incredibly, the occasional seal, speculatively venturing this far up the Yarra.

Under community stewardship, the conservation and restoration of the former convent has been conducted efficiently and gently. This time, traces of the past have been preserved – such as the original fittings made from Australian timbers but carefully painted in the monastic era to simulate richer and starker European grains.

Restored spaces have been activated as studios, cafes and venues for art, music and theatre. The courtyards, gardens and meadows are now prized as a different kind of refuge – a series of crucial, inner-urban, freely accessible open spaces. The site did not become a gated community, and nor is it a partitioned one. And there is no mini-golf to be seen.