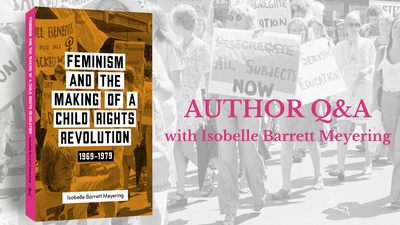

Q & A with Isobelle Barrett Meyering—Author of Feminism and the Making of a Child Rights Revolution 1969–1979

The late 1960s and 1970s were a period of unprecedented youth unrest and rebellion. This era produced a revolution in our thinking about children’s rights: radicals demanded not just basic protections for children, but their liberation from adult power in all its forms.

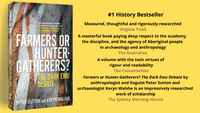

IMAGE CREDIT: Mitchell Library, SEARCH foundation

When Australian women's liberationists challenged prevailing expectations of female domesticity, they were accused of being anti-mother and anti-child. Feminism and the Making of a Child Rights Revolution provides a much-needed reassessment of this stereotype, shedding light on the movement's expansive vision for social change and its lasting impact on the way we view the rights of women and children.

Isobelle Barrett Meyering is a historian of Australian feminism, childhood and the family. She is currently based in the Department of History and Archaeology at Macquarie University.

1 What was the child rights revolution? What were they fighting for?

The late 1960s and 1970s were a period of unprecedented youth unrest and rebellion. This era produced a revolution in our thinking about children’s rights: radicals demanded not just basic protections for children, but their liberation from adult power in all its forms. Women’s liberationists were at the forefront of this new wave of child rights activism and spearheaded campaigns on issues ranging from childcare and sex education to family violence and child abuse.

2 How did you come to write this book?

The book began as my doctoral project. Some of my ideas and arguments have shifted over time, but the core motivation behind it remains. I wrote the book because I felt it was important to challenge a pervasive stereotype of women’s liberationists in the 1970s as uninterested in children or even anti-child.

3 What has been the highlight for you in the process of writing and researching?

I am a compulsive researcher and always enjoy the hunt for new archival sources. Historians of the Australian women’s liberation movement are fortunate to have access to numerous collections gathered carefully by activists over the years, and writing this book gave me the chance to travel around the country (pre-COVID, of course) to find out what they revealed. Following this paper trail was often time-consuming but led to some rewarding discoveries, including evidence of children’s own political activities.

4 Tell us about your writing routine. Where do you like to write? When and how often?

I benefit from the sense of momentum and focus that comes from working intensely on a task and prefer to write in blocks. Depending on the project, I will dedicate a week (or several weeks or months) to work on a piece of writing; inevitably, it almost always takes longer than planned. As for where – I like the idea of working in cafes or libraries, but am more productive if I write in a dedicated (and quiet) space. Like many people, for the last two years that has meant working for the most part at home, at my dining table. I’m not planning to make this a long-term habit.

5 What was the most surprising discovery you found through your research into feminism and children’s rights from the 60s to 70s in Australia?

It was my initial discovery of North American radical feminist Shulamith Firestone’s theory of children’s liberation that first piqued my interest in this subject. Her bestseller, The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution (1970), featured a dedicated chapter on children’s oppression and she concluded the book by demanding nothing less than their full autonomy. Given the emphasis that Firestone placed on children’s liberation, I was more than a little surprised to find that this aspect of her remarkable book was rarely mentioned in movement histories, despite the formative impact that it had on Australian activists, as I detail in the first chapter of my book.

6 What message do you want to leave with readers of your book?

I want readers to come away with a deeper appreciation of 1970s feminists’ expansive vision of social change, the vital place that children occupied in this vision, and the sheer time and energy that went into putting it into practice. I’d also like to think that the book provides an opening for further critical reflection on the way we frame children’s rights today and the need for a more considered political response to children and young people’s own demands on issues ranging from LGBTQIA+ rights to climate change.