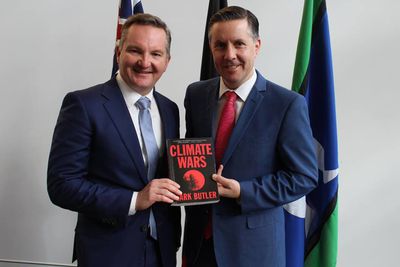

Chris Bowen launches Mark Butler's new book Climate Wars

A forceful case for using less and cleaner energy as part of global action to save the planet.

Chris Bowen did the official honours and launched Mark Butler's new book Climate Wars on Monday this week.

Verity Firth, Professor Stuart White and Louise Adler spoke at the launch, which was held at the University of Technology Sydney. You can read Chris Bowen's speech here.

In the book Mark Butler makes a strong case for a change in environmental policy, which he discussed at the launch. He has kindly allowed us to publish his speech from the launch here.

Thank you Louise, thanks very much for that kind introduction and to Verity for your warm introduction.

Thank you so much to UTS for hosting us this morning. To your warm acknowledgement of country, can I repeat my respect for elders past and present, the Gadigal people of the Eora nation.

Can I thank particularly the Institute for Sustainable Futures whom I have met with a number of times now in my four years of turmoil in this portfolio. It was great again to have some time this morning talking about the exciting research that you’re doing at this university. So thank you very much to the UTS for hosting today’s events.

Thanks particularly to Chris Bowen for that very warm introduction and launch. Chris is a close colleague and friend, and a fellow member of the Adler stable. It’s a broad church, Louise’s stable, but Chris and I are very proud members of that stable.

But for today’s purposes, other than being a friend and colleague, I wanted Chris to launch this book because he really is the principal guardian of the proud Hawke/Keating legacy of Labor economic reform. Both of us see this policy area not just as critically important in preserving our natural environment, but predominantly a major piece of economic reform in that proud Labor tradition.

I want to thank everyone else for coming, obviously, Richard, another close friend and colleague, Craig, who sat next to me in the Cabinet, or I sat next to him, I think I came in much later, while we were working through some of these issues in the Gillard Government, and state colleagues, friends from the environment movement, the NGO sector, my mum – not necessarily in that order of importance obviously – all of you, thank you very much. It’s a great privilege that you’ve given me to come along.

I particularly want to mention Alzheimer’s Australia. Sue Pieters-Hawke doesn’t appear to have been able to make it this morning, but I’ve been talking to her over the last several days.

I do see writing books, as Chris does, I know, as part of the vocation of being a politician, of being a public figure. Even in the digital age, writing a book is still the only way in which you are able to put out an extended argument in a critical area of public policy. But there is still, in spite of the best efforts of some of us, not a strong tradition of writing our own books, other than autobiographies or polemics about your party in this country. I think that’s a pity.

It’s not the case in the UK, it’s not the case in the US, where I think it is much more seen as part of your job, part of your vocation as a senior public figure, to write about ideas. I think that would be a good thing for Australia if we presented that as part of our job.

As with my last book, I am donating my royalties – if anyone buys this book of course, which may be presumptuous – to the Hazel Hawke Alzheimer's Research and Care Fund which is run by Alzheimer’s Australia, and which I see as a really worthy institution to receive the proceeds of any sales of this book.

But the story, I guess, for me, in this book starts 10 years ago when public support for action on climate change was the highest that it has been for the past quarter of a century.

Kevin Rudd, famously, gave voice to that depth of feeling when he described climate change as the greatest moral, economic, and social challenge of our times. And eventually, even the nation’s biggest climate curmudgeon, John Howard, yielded to this sentiment and promised to introduce emissions trading scheme, at the 2007 election, by 2011.

But the hope of 10 years ago has been relentlessly battered by a decade of reckless vandalism – vandalism led overwhelmingly by Tony Abbott, but with the assistance of a number of his political colleagues, by the right wing media, and at times also by business figures who, frankly, should have known better.

As Chris said, the scientific consensus about climate change, and particularly the role of human activity in driving it, is undeniable. But still, under pressure over the Government’s cuts to CSIRO funding last year, the Leader of the Government in the Senate, George Brandis – who apparently, Christopher Pyne tells us, is what the Liberal party calls a ‘leftie’ – described the science as not yet settled.

Now, I just don’t understand how a Leader of the Government in 2016 and 2017 can still say this.

As Chris Bowen just pointed out, 97 per cent of climate scientists who publish in peer-reviewed journals in this area, agree with the consensus position now, recognised by the Australian Academy of Science, the CSIRO, the Bureau of Meteorology, and all of their equivalents overseas, that climate change is real and is being driven by human activity.

As Chris also said, they ascribe the same level of certainty to that conclusion as medical scientists ascribe to the connection between tobacco use and lung cancer.

While the scientific opinion has only gotten stronger, the impacts of climate change have also started to unfold before our eyes, only the most dramatic example of which is the devastating bleaching events that have occurred on the Great Barrier Reef over the last 18 months.

While the climate wars have raged in Australia, the rest of the world has started to take real action.

The international business community has moved.

In 2015, for the first time ever, investment in renewable energy was greater than the combined investment in coal, gas, nuclear, and hydro power, and it is always going to be that way into the future.

Governments from Canada to India, from Britain to China, and the vast majority of the American states still, in spite of Donald Trump, are acting too.

And, six years on from the division and disappointment of the Copenhagen Conference in 2009, the Paris Agreement finally charts a path, signed up to by all nations of the world, for global action by this generation.

But those realities are relentlessly shouted down by the Coalition’s right wing, and much of the Australian commentariat. Even the more moderate voices, like the Prime Minister, try to walk both sides of the street; pretending that we can meet our commitment to future generations while clinging to the economic status quo.

So while corporate boardrooms and governments across the world are shifting to a low-carbon future, Australia’s public discourse focuses on opening up new coal mining regions to compete with existing operations over a shrinking global market for thermal coal.

They focus on winding back the Murray-Darling Basin Plan, in the face of clear advice from the CSIRO and the Bureau about the dramatic decline in stream flow and rain fall in the Basin.

They focus on expanding broad-scale land clearing in north Queensland, including in Great Barrier Reef catchment areas. We continue to hear repeated calls to abolish the Renewable Energy Target, to revisit our Paris Commitments around carbon-pollution reduction, and to build new unabated coal-fired power stations.

Frankly, it’s no wonder that so many younger Australians – and some that aren’t so young – look on in astonishment and increasing anger as our generation of politicians indulges these anti-science, selfish agendas – guaranteeing that the impacts of climate change and the costs of adjustment will be so much more serious for our children and our grandchildren than they would be if we simply did the right thing.

They are surely going to curse us in years to come.

What makes me angry is that, with political will, Australia could be leading the world in innovation, in investment and jobs, and in discharging this generation’s responsibility to the next – instead of ranking number 60 in the 2015 Climate Change Performance Index out of 61 nations, ahead only of Saudi Arabia.

But, in spite of the turmoil in British politics, which Chris alluded to, it’s that little island which gives me hope.

That little island where the sun shines about three days per year, but which managed to install four times as much solar power in 2015 as this vast, sunny continent.

Where they’ve already cut their carbon pollution levels since 2005 by 30 per cent, and will do so by 60 per cent come 2030. Just as a comparison, the Turnbull Government’s data, which was released just before Christmas, projects that Australia’s reduction on 2005 levels by 2030 will be precisely zero.

The UK has managed a profound transition through the bipartisan consensus, or tripartisan consensus for a while, that Chris talked about, which survives the current political turmoil in that nation that swirls particularly around Brexit.

And they've done it while still producing three times as much steel as Australia produces, and with a car industry in that country that employs some 800,000 workers; showing that you can get deep reductions in your carbon footprint while maintaining an industrial base.

But to do that, we have to take on the loud minority that wants to keep us at the back of the pack – to forge the sort of consensus that you see in the UK and many other countries that recognises the necessity, and also the opportunity, in shifting to a low-, and ultimately no-carbon economy.

And the book makes the case that Labor has the credentials and the experience more than any other Australian party to lead that transition.

We’ve certainly made mistakes in this policy area over the last 10 years, at times in the presentation as well as the design of our reforms.

But we have learned the lessons of those mistakes – we have been honest about them, as well as being proud of what actually worked.

This transition must be, to use the words of the Paris Agreement, a Just Transition.

While the label that was adopted in Paris might be new, this was the approach of Hawke, of Keating, and of John Button, in the car plan, in the steel plan, in the waterfront industry reform plan, and in many other areas of reform through those proud Labor years of the 1980s and 1990s.

They developed a clear plan, negotiated with stakeholders In those industries.

They developed a support plan for workers who were impacted by the transition, and they put in place genuine investment to diversify local economies, particularly regional local economies that were impacted by change.

It’s an approach that requires hard work by governments working with business, with unions, and with local communities, and that sort of work has always been a core part of the Labor mission.

While the key purpose of the book, obviously, is to burnish Labor’s credentials and our policies, my real hope is that it will reinvigorate some momentum and discussion around real action, as well as generating some hope that our political system can actually deal with change that matters.

In closing, can I again thank MUP.

They are a great publishing house to work with; particularly Louise, but Sally Heath and her team also are a sheer pleasure to work with.

I also want to thank a range of my colleagues and many others outside the parliamentary system who took time to read some of my drafts and give me very frank, very fearless, and at times quite biting advice, maybe about my grammar, but also about the content. It really was a wonderful process, having that dialogue with so many of you.

Most importantly, to my family who tolerate my writing over summer holidays. It really is a constant source of wonderment to me their tolerance of this quite bizarre vocation Chris, Richard and I have chosen. Thank you all for coming along today, it really is a great pleasure to be here with you.

Mark Butler MP is the Shadow Minister for Climate Change and Energy and national president of the Australian Labor Party. Climate Wars is out now.