←Back to Whiteley on Trial

An extract from “Whiteley on Trial”

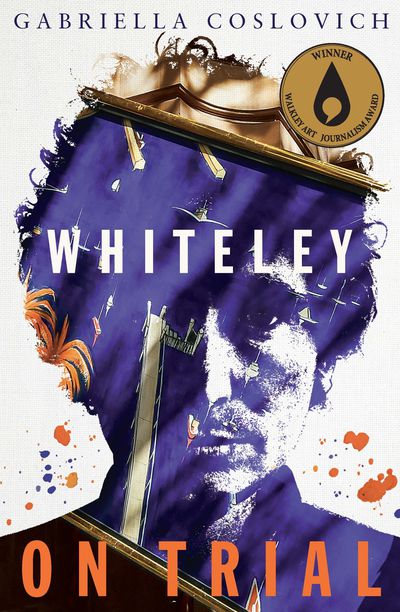

Works by Brett Whiteley, once the enfant terrible of the Australian art scene, are now a blue-chip investment. The artist died of a heroin overdose in 1992, but he continues to make headlines. In her book, Whiteley on Trial, journalist Gabriella Coslovich investigates a multi-million dollar case of alleged art fraud that centred on two paintings, both purportedly by Whiteley. The case was finally closed in mid-2017, but in this extract from Part I of the book, Tell the Truth, reproduced here with permission, Coslovich takes us back to the beginning.

Part I: Tell the Truth

‘I WAS JUST NEVER sure what I’d seen. I’m not saying I’m sure now.’

To the casual observer it would have seemed the most innocuous of things, a cluster of unfinished paintings, impressions of Sydney Harbour. But what Jud Wimhurst saw and how he made sense of it would shadow a decade of his life, consume the art world, and lead to Australia’s most significant and ultimately controversial examination of art fraud. What he saw was never far from his mind.

‘I wished I hadn’t gone to work that day,’ he said. ‘As soon as I saw it, everything changed.’

I was asking him to tell me again what had happened. We were both trying to understand it, to resolve what we’d heard in court with what we knew, or thought we knew. His voice was earnest and candid, the voice of someone who told stories straight, even when there was nothing straight about them. We were sitting around the corner from the now headline-making studio where it had happened, having coffee at a footpath table, taking in the morning sun and exhaust fumes. Wimhurst was an easygoing, young-looking 42-year-old, with plump skin and black-rimmed glasses, neatly dressed in black—cap, t-shirt, sneakers—and loose-fitting, rolled-up denims with a long silver key chain trailing from a pocket, a look that suggested his skateboarding past. He was an artist and had a musketeer-like goatee. We had spoken several times by phone, but this was the first time we’d met; the only time I’d seen him other than when he stood in the witness box. Trams rattled by as he took me back to that grey winter’s morning ten years earlier in 2007.

As usual, he had been the first to arrive at his work, in the industrial and gentrifying inner-Melbourne suburb of Collingwood.

Victorian Art Conservation was housed in a double-storey, red brick warehouse in Easey Street, a street synonymous with the city’s history of crime. Wimhurst had worked there for just on two years. His priority was his art, but art didn’t pay the bills. So three days a week he made frames, stretched canvases, varnished paintings and built plinths for his boss and owner of the business, Aman Siddique.

A painting restorer of high regard, Siddique generally left Wimhurst alone to do his work. This suited him and despite Siddique’s sometimes gruff manner and occasionally explosive temper, Wimhurst genuinely liked him.

‘I did like him. I respected him and maybe the liking him was because I respected him. I was there to learn and he was happy to teach me.’

Siddique had also been kind to him when his father was dying of cancer, giving him as much time off as he needed. This happened in the first month of him starting work there and had left him feeling loyal towards his boss. He loved too that at Siddique’s he had the chance to see the work of Australia’s prime artists at close range.

‘That felt like a great privilege, to be honest. It was anyone and everyone, but it was always interesting for me when something of note came in, so when Gleesons came in I liked that, when Arkleys came in, when Whiteleys came in, when Tuckers came in, things like that, your classic Australian artists, it was great for me to be able to see those paintings.’

But the paintings he saw on this particular morning would shatter his faith in the business. Just before 10 a.m. he unlocked the building’s fortress-like red front door and began his daily routine: security system off, lights on, check the answering machine on the second floor. When he reached the top of the metal stairs he saw that something was different. Directly in front of him was Siddique’s desk, to the right, the retouching room, and next to that a smallish storeroom. Wimhurst had never seen the storeroom open and had often wondered what was in there. What was so important that it needed to be locked away? Valuable artworks, some worth millions, were continually passing through the workshop to be cleaned or restored. Paintings were left out overnight. There was no need to lock them up—the security system was first rate. Today the twin sliding doors of the storeroom were wide open.

The sight jolted him—had there been a break-in? Unlikely. He had just turned off the security system. He walked towards the storeroom and glanced inside.

‘I didn’t walk all the way in and I didn’t necessarily want to walk all the way in,’ Wimhurst told me. ‘I didn’t even want to see what I’d already seen.’

It looked as though someone had been interrupted in the middle of a job. There were several paintings in progress, brightly coloured in blues and yellows, scenes of Sydney Harbour, which he instantly recognised as in the style of Brett Whiteley. He also noticed a paper cut-out of a vase lying haphazardly on the storeroom floor—a vase of similar shape and size to one he had seen in the foreground of a Whiteley painting that had recently come into the studio; an unusually bleak, predominantly brown painting of Sydney’s Lavender Bay, that had not been locked up and that was always getting in the way. Siddique had asked him to remove that painting’s frame. What was going on? Why were these Whiteley-like paintings being made? He knew that Siddique would occasionally conduct little tests in the style of an artist whose work he needed to conserve, but there were too many unfinished paintings here for it to be simply an experiment.

His boss could turn up at any moment and he didn’t want to be caught looking at this place that had always been off limits. He went quickly back downstairs and got to work. But he could not put those paintings out of his mind. What reason could there be for them? It was hard for him to come up with many legitimate motives. Should he confront Siddique? And say what? It wasn’t a crime to copy an artist’s work, was it? Later that day, after Siddique had turned up, Wimhurst went back upstairs and saw that the storeroom was once again locked. He told no-one what he had seen. But had he been right to say nothing? Should he have given Siddique the chance to explain?

Wimhurst began to suspect other things at Easey Street—the arrival of timber panels of various sizes, some huge, others smaller. A group of these had been stacked up against Siddique’s desk. Siddique had brushed off his questions about why they were there. They belonged to Peter Gant, Siddique had said, referring to the art dealer who was often around. Why, then, had they been delivered to Easey Street? They were doors for Gant’s house, Siddique told him. Was Gant building a house for dwarves? Wimhurst had cheekily asked. Siddique chuckled and said no more. The doors disappeared soon after. Wimhurst was not alone in knowing that Whiteley would sometimes paint on smooth-faced wooden doors.

A few weeks after finding the storeroom unlocked, Wimhurst’s workmate Guy Morel showed him something that added to his disquiet.

Morel was a bookbinder and paper conservator who worked upstairs at Siddique’s studio. Born in the Seychelles, Morel was a big- hearted man with a nervous manner; he had the trace of a French accent and would stutter when anxious. He had first met Siddique in the 1980s, when Siddique was working as a painting conservator in the regional Victorian town of Ballarat. In the early 2000s, Siddique invited Morel to set up a workspace at his Easey Street studio. Morel would divide his time between Easey Street and his home studio in Brunswick. The two were always bickering about money.

On this day, Wimhurst was working upstairs when Morel called him over. ‘Have you seen this?’ he asked, holding out a scrap of paper filled with the signature of the Australian painter Fred Williams, as if someone had been practising the name again and again. The sight of these signatures made Wimhurst break his silence.

‘I just said to him, “Have you seen the Whiteleys floating around?” because, you know, if there was nothing to be ashamed of they should have been out at some point. And he hadn’t seen them. So that’s when I told the story.’

Morel decided to look for himself. The storeroom’s 2.5-metre- high walls did not reach to the top of the warehouse ceiling, so Morel placed a chair on the workbench adjoining the locked store- room. Digital camera in hand, he climbed onto the chair and hung his camera over the edge of the storeroom walls. When he looked at the camera’s screen he saw what had been troubling Wimhurst for weeks.

Whatever was happening at Easey Street, Wimhurst wanted nothing to do with it. His artistic career was on the brink of taking off, and he needed a bigger home studio than he could afford in the city. He reasoned that he could use this excuse to quietly depart without giving his real concerns to Siddique. By the start of spring in 2007, Wimhurst had left Victorian Art Conservation. Morel stayed on and promised to ‘keep an eye on things’. Wimhurst moved to the country with his partner and dedicated himself to his art. But the move did not quarantine him from the activities at 26–28 Easey Street.

‘I wasn’t completely surprised when I got the call,’ Wimhurst explained when we met. ‘I had a feeling something would happen at some time, if what I saw was what I thought it was. And I always hoped it would never surface, and I was wrong.’

The call came in 2014. Siddique phoned Wimhurst telling him that he might soon be hearing ‘bad things’ about him, and that the police might come calling. Wimhurst asked what he should do. Siddique answered: ‘Tell the truth.’

In 2016, Wimhurst told his story in the Supreme Court of Victoria— or at least as much of it as the law would allow. We had both been staggered by the restrictions placed on what witnesses could and could not say; he as a witness and I as an observer wanting to write a book on the case.

‘That was a shock,’ he said. ‘I thought the idea was to get to the bottom of the truth, but that’s not necessarily the case. It’s a lot more complicated than that. I understand now that it was also about Peter and Aman feeling they’d had a fair trial. But I also feel, was it a fair trial if so much was left out? I don’t know.

‘It makes me feel really quite confused, the whole situation. It’s hard. I want to believe the best but I’m not sure I can do that. And I don’t know whether talking to Guy was the right thing to do but I felt that I needed to do something, and I needed another opinion. There was no-one else that worked there except me at that time.’

I asked him to describe once more the paintings he’d seen in the storeroom. He had consistently told me that they were yellow and blue, and yet, the paintings that had ended up in court were orange and blue. Was he sure he’d seen yellow?

‘I really don’t know,’ he said. ‘I remember seeing yellow so maybe I’m remembering it incorrectly, or it was underpainting. I mean they were in early stages. There’s so many reasons why they could have changed. I also remember them as being smaller.’

He couldn’t even say for sure whether the paintings he saw were the same ones that had ended up in court.

‘I know that doesn’t link up, but I think maybe I might have seen some that were test pieces or something like that. Or ones that weren’t good enough. They did seem to be painted on those door panels that had been delivered. They were smaller than full door size, maybe a bit wider, they weren’t as large as the ones in the courtroom, so I don’t know. I know these things don’t match up, I might have seen something different, but I’m just saying what I saw. I wish I had the definitive … but I don’t.’

A week after our meeting, there would be a definitive answer.

The Court of Appeal would rule that the jury that had found Aman Siddique and Peter Gant guilty on three counts of art fraud had got it wrong. That it was not possible to find the men guilty ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ on the evidence presented to the court. It was an exceptional ruling in a judicial system that considers the role of the jury utmost. Significantly, the appeal judges made no finding on the authenticity of the paintings. So where was the truth in this story?