←Back to Take Heart

An extract from “Take Heart”

Bill and I met through work, when he and I were speaking at a resources industry conference.

As the head of the Australian Workers’ Union, he was the headline act, talking to hundreds; and I was off-off-Broadway, in a steering group.Listening with my boss to his address about people and work in the future, I agreed with his central premise but felt he hadn’t made enough of the importance of women’s emergence in the workforce, and, afterward, I told him.

The following year, our paths crossed again when he was travelling to mining and manufacturing sites to talk to union members about government policies and I was working for Australia’s largest manufacturer of cement.

Bill had become very well known in Australia as a union leader in 2006, when the Beaconsfield mine collapsed and two men were trapped and another killed.He became the conduit between the people on the ground and the rest of the country, who were watching it unfold on their TVs.

I was in the slow and difficult process of separation from my first husband, and it was a very stressful time for my family.

My children and I moved into a place a few streets away from the family home. They went back and forth but mostly were with me, being so young.It was very important to me that they were connected to their dad. We lived like this for almost a year and a half before I decided my future was with Bill.

Living through that period was tough for all of us. The pain, loss, disruption, the difficulty for the children; trying to live in two homes, the economic losses. And living it through the lens of a camera was a particular trial. I wonder if the public nature of my divorce and remarriage compounded the anxiety I felt.

But this also led me to think the stigma associated with, and stereotyping of, remarriage might hinder the establishment, strength and wellbeing of blended families, and was when I started scouring academic journals. Looking back, I think it was this that gave me the courage to write about the topic.

Because my parents were so (comparatively) modern in their way of thinking, I was a bit naive about some of the assumptions, stereotypes and judgements associated with working motherhood, because it was the norm in my home, both growing up and while I was married.

But when you go through the process of getting unmarried, and then marrying again, all your choices, including all your parenting choices, are under a lot of scrutiny, by others and yourself.

It can be a bit of a shock to the system to feel you suddenly have to explain yourself and your decisions to everyone around you—counsellors, lawyers and other outsiders. While you might be doing a great job as a married mother, you’re doing it unobserved, but when you separate, you become more conscious of every little thing, even if nothing about your parenting has changed.

The upside for me was seeing what I could do better for my children, because everything became more magnified; it super-charged my motherhood like an electric shock. I became fierce and defensive about my mothering and my role as primary carer of my children.

Because they were going through a major life transition, I became laser-focused. For a while, I was hyper-vigilant with mothering and probably overdoing it. But because I was made aware that what I was doing was outside the norm, I felt the need to compensate.

Another sign of just how strong are the underlying assumptions about what is the right and conventional family model is the high level of interest people have in someone else’s separation.

This was heightened, of course, in my case because the media reported on my personal life but it happens to a lesser, but no less real, extent to everyone.

It’s that kind of ‘car crash’ mentality that is hard-wired in us; that when we see an unexpected fate befall someone, part of us is compelled to look. Rather than us just being gawkers, though, it becomes a matter of ‘What can I learn to avoid it happening to me?’.

While this is a self-preservation instinct, it puts pressure on the family under scrutiny and can add to its isolation at a time when the community ought to protect it. Again, there were no easily available resources to help prepare me for this.

I’m not a clinician or a step-family researcher, so my contribution is my personal—deeply personal—experience. I’m making it only because I want to talk about the children in these common if ‘unorthodox’ family situations and promote their welfare and wellbeing.

Since becoming part of a step-family, I’ve felt deeply some of the intense bias against, and stereotyping of, these family arrangements, as I’ve met and talked with mothers and fathers around the country. Old myths and fairytales about ‘wicked’ step-parents still cast a shadow over the chances of success for people entering second marriages.

I believe there is a tendency to view families formed by second marriages and involving children as ‘less than’ families consisting of married parents raising their own biological children. This can make those families seem more vulnerable.

We mustn't squander any more time on the myth that second families, or other non-nuclear groups, have any less claim to the word ‘family’ and all it stands for.

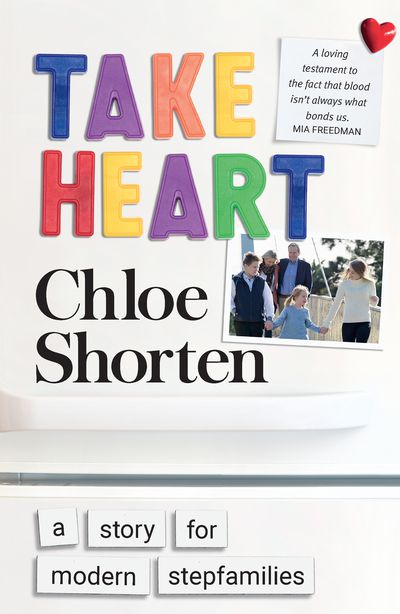

Take Heart is out now.