←Back to Margaret Preston

An extract from “Margaret Preston”

For Margaret Preston modernism was a set of ideas and practices directly embedded in everyday life, and inextricably connected to her lifelong interest in the applied arts, or crafts as they are more often described. The common factor uniting all the media in which she worked, according to the historian Humphrey McQueen, was ‘constant improvisation … she was confronted with an endless sequence of problems in her daily activities’.

Increasingly she had come to view oil painting as a superficial activity and a less technical proposition after it was possible to achieve colour by mixing rather than glazing (an advancement of the nineteenth century). Preston’s craftwork ‘helped her to realise that it was what lay underneath that mattered’.

Over the years she practised the arts of pottery, printmaking (woodblock printing, silkscreens, monotypes and stencils), basket weaving and textile design; all were eminently suited to carrying out at home, a point Preston emphasised time and again in the many ‘how-to’ articles she published to inspire women in particular to improve their lives by making art.

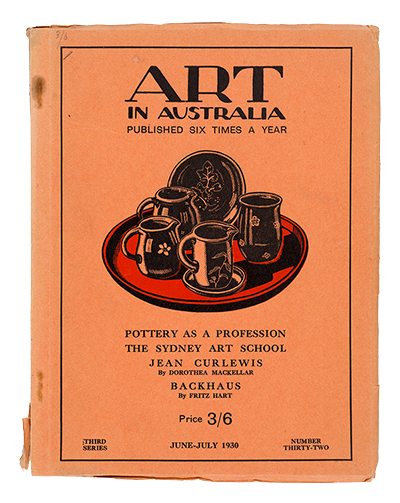

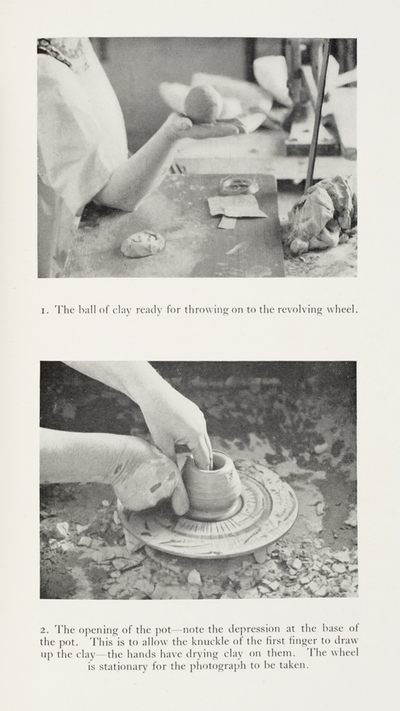

This ambition is insistently felt in her 1930 article for Art in Australia, which extols the virtues of pottery as a profession. With a wood kiln — ‘no bother’ for the potter herself to construct — and access to clay for the digging, the path to becoming a fully-fledged practitioner, she explains in her exposition, is just three main steps away: cleansing, sieving and wedging the clay; making the pot; then undertaking the firing.

Though at best a résumé of the craft, Preston’s aim was to make potting sound as agreeable and achievable an activity as possible — even if with a small but stern caveat: ‘As to the strenuous part of the work, if anyone knows any successful work that is easy, don’t waste time reading this’.

Departing from the usual reportage and opinion format of Art in Australia, her text is accompanied by photographs of both hand-built and thrown techniques to further illuminate the methods described. Finished works by Australian studio potters complete the lesson, with tableware by Gladys Reynell and her Osrey Pottery of Ballarat, together with Preston’s own cheerful teapot and vase.

Preston was also alert to the ceremonial aspect of ceramics and their place in long-held traditions across many cultures, later taking ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation) listeners through a history of utensils and pottery. To promote her talk on radio she selected images of women’s pots from ancient Egypt, ‘primitive’ vessels carved by Pacific Islanders, Greek amphorae from the British Museum, Spanish maiolica ware, and modern British designs.

In discussing the revival of studio pottery and the backlash against mass production she singled out the ‘faultless creations’ produced in the studio of the Martin Brothers in England, having viewed fine examples of their salt-glazed stoneware at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Aside from the bespoke nature of the pottery, the exquisite surface decoration of Martin ware appealed greatly to Preston, who shared the brothers’ great admiration for the woodblock prints of the Japanese masters, Hokusai in particular. The four Martin brothers established their business in Fulham in 1873, each one taking exclusive responsibility for an aspect of the production. But with such specialisation came limitation, and their great distinction became their downfall; when the third brother died the studio closed.

Preston was of the view that a good potter must maintain contact with the entire process, from beginning to end, a practice more in line with the Bauhaus method, in which the artist was trained to complete each stage themselves, from design through execution. Still, the Martins’ unyielding commitment to artisan values left an impression on Preston, and she would go on to advocate for the development of a craft or studio pottery industry in Australia. ‘Only original work should receive applause in such a young country’, she wrote. ‘Just get to it, someone, and originate’.

The article inspired at least one conversion. Writing to Selma Heysen in Adelaide, wife of the painter Hans Heysen, Preston passed on the names of two textbooks for pottery (Emile Bourry’s Treatise on Ceramic Industries from 1901 and The Potter’s Craft by Charles Binns, published in 1910), and suggested that Selma see Miss Symons, a South Australian potter of experience. ‘Pottery is far better fun than painting’, she said, but also warned, ‘if you help David you will desert your Hans — so beware’.

By contrast, Preston’s description of basket weaving was infused with the therapeutic and rehabilitative qualities of the art form. The simplest of all crafts, it was to her mind ‘possibly the most useful. It helps the hands that have become stiffened through various causes, it is a very quiet occupation for the nerves, and for the making of simple objects only a few rules have to be remembered’. Moreover, it was a craft of ‘feeling’ and touch over seeing. Also appealing was the simple equipment required. For non-commercial work only a sharp pocket knife and gardening snips were needed; for commercial work an outlay of around ten shillings would procure a bodkin, pricking knife and basketmaker’s iron to draw the weaving closer together. Detailed instructions with diagrams followed, along with fine examples of work by Preston and artisans of various nationalities, as well as a returned soldier.

Outside painting, Preston’s chief interest was printmaking, specifically the ‘friendly little craft’ of woodblock printing. After having learned the process in England she took it up with great zeal in the 1920s, producing many outstanding works of art. She quickly became expert, preferring to cut along the grain of the wood, print in black and hand-colour her images in the Japanese manner, rather than work with multiple colour blocks. Preston was one of the few Australian modernists to find inspiration in Asian culture; for the majority of artists, ties to Europe and the training available ensured that the western lineage of art remained central to Australian developments. To further her competency and understanding of Japanese printmaking, she and Bill took a trip to Kyoto in 1934, where she studied the techniques of woodcutting with the son of the renowned artist Hiroshige.

Preston also liked to print by hand rather than use a press, noting that ‘with work done in this way there is a certain artistic value gained that is lost with any touch of a machine’. The list of tools for the more experienced woodcutter is in keeping with her notion of the ‘friendliness’ of the art form, and especially appealing: wood of Turkish box, sycamore or cherry, Tasmanian beech or Huon pine, her personal favourite; a three-cornered Japanese knife, gouges and a small wooden hammer; Indian ink or black oil colour; dry watercolour paints with rice water; and squeegees, baren and flat tray for printing.

The design of the print was key — the simpler the better in Preston’s view. And she emphasised the handmade aspect, seeing wood whittling as an especially satisfying activity that also had great aesthetic rewards, the qualities of which are otherwise lost in commercial propositions.

The National Gallery of Australia’s splendid catalogue raisonné of Preston’s print oeuvre by Roger Butler shows that woodblock prints comprise the greatest proportion of her output, and among the most exquisite. Her Wheelflower (c. 1929), Birdofparadise (1925), Redbow (1925) and Mosman Bridge (c. 1927), in which she ‘put Sydney’s environment through a Japanese sieve’, are among the best recognised images not only of Preston’s work, but of twentieth-century Australian modernism. Just as the Japanese forged a national and egalitarian art via their ukiyo-e prints, Preston thought of her woodblock prints as a democratic creative platform.

Thea Proctor — who was introduced to the medium by her friend in the mid 1920s — commended her for her vision: ‘Australia should be grateful to Mrs Preston for having lifted the native flowers of the country from the rut of disgrace into which they had fallen by their mistreatment in art and craft work … Her gay and vivid woodcuts of native flowers, original and beautiful in design, are an ideal wall decoration for the simply furnished house’.

Printmaking offered both inspiration and respite for Preston. The translation of a motif to the clean lines required for woodcutting ensured she was constantly refining and clarifying her visual ideas for pictures, working out the best way to express them. The manual and procedural aspects of printmaking also seemed to help her broader practice, and even her mental health: ‘I find it clears my brain’, she explained. When the labour involved in cutting the blocks fatigued her hands Preston made monotypes and stencils, finding them particularly suited to capturing the feel and look of Indigenous painting, an aspiration that became especially compelling after her travels through outback Australia in the 1940s.

She also tried screen-printing, seeking tuition at the Mosman Art School in 1945, and soon after publishing an overview of the art form in the Society of Artists annual. Once more, materials, instructions and diagrams provide a step-by-step guide to undertaking the art at home, from how to make a screen and what paper to use, to both stencil and freehand methods.

This medium had a further application when Claudio Alcorso, chairman of Silk and Textile Printers Limited, invited Preston to develop a fabric design suitable for furnishings and fashion. Preston was one of thirty-three artists commissioned to create fresh, original patterns with an Australian spirit for the company’s new Modernage range, which was intended to bring Australian textile designing up-to-date and make it ‘consistent with our times’. Russell Drysdale, James Gleeson, Donald Friend and Jean Bellette were just some of the pool of impressive talent selected. The artists were not paid upfront, but received a royalty per yard, thus sharing the risk — and profit — with the printer.

Sydney Ure Smith remarked that the Modernage project was landmark in that it was the first time that Australian artists had been so comprehensively engaged to produce textiles which would rival and surpass imported designs. He also believed, like Preston, that handcrafts and applied arts could introduce creative thought and beauty into the functional items of daily life. Preston refused to differentiate between the fine arts, crafts and design, and was inclusive of the routine activities of creativity, from cooking and flower arranging to interior decorating, maintaining that the expression of modern life and cultural advancement was in the hands of all Australians, not just a chosen few.

‘Not all artists are able to write what they feel’, Hal Missingham later remarked; ‘Margaret does it unequivocally’. As well as being an outlet for Preston’s closely held beliefs, the process of writing her series of instructive texts allowed her to continue teaching, for which she had both flair and enthusiasm, long after she gave up conducting classes in the studio. Even the professional contingent at the Society of Artists was not exempt from a lesson in preparing their supports, grinding their colours, and mixing their mediums and varnishes.

Preston was a lifelong student of art herself, and the drive to document and disseminate her understanding of its history and modern applications also saw her carry out a program of lectures and practical demonstrations over the years, at the Society of Arts and Crafts, the Art Gallery of New South Wales, and the postwar Studio of Realist Art, to name a few. Those lectures that have survived in transcript reveal Preston to be a canny synthesiser of great swathes of material, moving her way through centuries, art movements and styles with demonstrable concision, and delivering her summations with the fervour of a missionary.

Yet she also recognised that encouragement achieved better results than demands, and she led by example. The great consistency in and connection between her art and domestic life, and her unremitting adherence to the still life as her subject, provided the solid grounding she needed to advocate for change.

This is an edited extract from Margaret Preston: Recipes for Food and Art.