←Back to From the Edge

An extract from “From the Edge”

Walking the Edge: South-East Australia, 1797

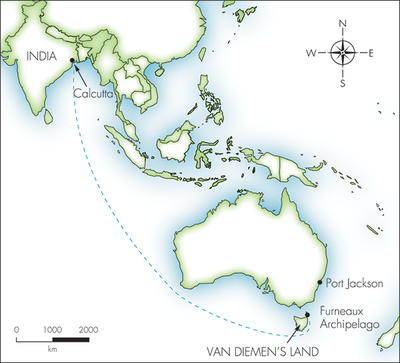

The wildness is ancient and humbling. Seen from offshore, the island barely rises above sea level, a lonely outcrop of monumenal granite and low-lying, windswept scrub that lies in a treacherous body of water off Australia’s south-east coast. On a clear day, when the white shallows appear beneath a translucent sea, it’s possible to imagine Preservation Island and the entire Furneaux Archipelago for what it is: the remains of the land bridge that once joined Tasmania to the Australian mainland some ten thousand years ago.

In November 2013, I came to this remote island off Tasmania’s north-east coast in search of a remarkable story of human endurance. After the wreck of the merchant ship the Sydney Cove in February 1797, this tiny island in Bass Strait—little more than three kilometres long and one kilometre wide—became the site of the first European settlement south of Sydney. Few Australians are aware of the story that unfolded from Preservation Island and even fewer are aware of its true significance.

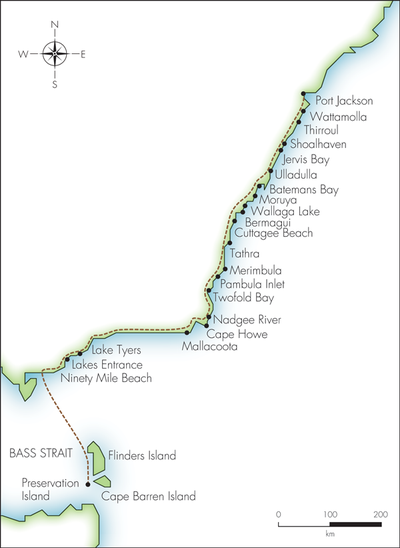

The first overlanders in Australia to pass through extensive stretches of Aboriginal Country have been largely forgotten. These men experienced the most sustained contact with Aboriginal people in the early colonial period beyond Sydney. Between March and May 1797, they traversed 700 kilometres of Australia’s south-east coastline, meeting and sometimes camping with Aboriginal people from at least eight distinct language groups between northern Victoria and Sydney.

Although the progress of their journey was recorded, sometimes in graphic detail, they were not funded by the state or charged with the duty of scientific discovery. In fact, most of them were not even European. The great majority of them were Bengali seamen, otherwise known at the time as ‘Lascars’.

For sixty-two days, five British seamen and twelve Lascars walked through what they saw as a nameless landscape.3 Aside from the sprinkling of place names bestowed by James Cook from the deck of the Endeavour in 1770—Point Hicks, Cape Howe, Mount Dromedary, Batemans Bay, Pigeon House, Botany Bay and Port Jackson—they had no other signposts to guide them. Indeed, many of the places they left behind them remained unnamed by Europeans until figures such as George Bass and Matthew Flinders followed in their wake. In any case, they had no authority to name. They were not explorers. They moved through the landscape not to discover but to escape, not for adventure but because of misadventure. And although they walked further on Australian soil than any non-Aboriginal person had walked before them, they remain today much as they appeared to the Aboriginal people they encountered along the way—apparitions, wayfarers who have yet to walk into history.