←Back to Dear Quentin

An extract from “Dear Quentin”

My mother could do anything. On Sundays she wrote letters at a large Indian teak desk trimmed with studded snakeskin in our living room, never used for any other purpose. On it a few photographs, flowers in a white jug, blotting paper folded, the usual accessories; a holder for paper and envelopes – but they were kept empty. Her stationery, bought at the Finney’s sales twice a year, stayed in its sturdy boxes in the drawers. My mother liked a soft cream, the colour of my own paper. Her envelopes were lined with nest white tissue. Her favourite brand was Elco from Switzerland, definitely no decoration, no deckled edge. She used an ordinary-looking push pen with a ‘J’ nib dipped constantly in and out of a bottle of Quink ink, never a drop spilt. My own is a small, heavy, black and silver Mont Blanc, one of my most treasured possessions. It was given to me by UNICEF some years ago when I did a handwriting project for them. I fly into a panic when I mislay it.

Each letter is precious to me, to open, to read and then to respond.

In my thirties, my letters changed; the personal became the political. Less about babies and the chaos of family life; more about community engagement, working with others for the things we wanted in our neighbourhood and for social and legal reform. Heady times. The women’s movement was energetic, organised and controversial. We were on the airwaves and television, and in the newspapers. For the first time, I received letters from people whom I didn’t know – at work and at home, some encouraging, supporting, others not, and so it has remained. Feminists have always been writers, of speeches, articles, opinions, advocacy.My appointment to the National Women’s Advisory Council in 1978 opened doors to me: to national and international involvement in social and political action to advance the status of women. I am deeply grateful for the opportunities I was given to participate, to learn and to make lifelong friendships that have enriched my life in immeasurable ways. The bonds we shared, the connections we made, the work we did grew from our meetings, storytelling, networking. They were strengthened and sustained by the letters we wrote. As Shirley Hazzard describes it in Transit of Venus, ‘Reform, my dears, is neither banners nor bombs. Reform is unpaid labour, is poverty, is solitude, is the composition of innumerable letters by the midnight oil and the engagement in ignominious struggles with a duplication machine.’Yes, mine is a generation of letter writers, just as my mother’s was. We write to our dear ones and people whom we admire to express our feelings on significant events in their lives. Some are dashed off, others are for keeping. I remember how much it meant to me in the tough gullies to receive a note of encouragement. ‘Thinking of you’ was all I needed to stiffen my spine when things went awry.

In 2003, I lived at Women’s College at the University of Sydney. I loved ‘my girls’ in that lively community of scholars. They shared my surprise and excitement at being appointed Governor of Queensland by Premier Beattie. From the day of the announcement at our beautiful Queensland Art Gallery in Brisbane, something marvellous started to happen. Letters poured in: advice, ideas, remembrances, photos from long-lost cousins. Many were handwritten, occasionally in that distinct, frail script of the very aged. I was deeply touched by warm sentiments, some in formal language, others in more familiar, even sentimental tones – from wits, sages and would-be novelists. I set to answering them, and I have been doing that ever since, writing by hand whenever I could because it seems to me more personal – conveying an intimacy and immediacy of thought. I like to think that as my hand holds my pen and moves across the paper, concentration and affection shape the letters, heart and mind blending in an art form as old as time. It has taken me a while to succumb to emails, but I use them sometimes for quick messages or when time is short. It’s often the way a correspondence starts these days. I’ll be keeping Australia Post in business for a long time yet though. There is still something special about ending a ‘real’ letter in my letterbox at the front gate. Oh yes, definitely.

Every message reached into my head and my heart, each one arming my determination to give my best every day, to make the most of a unique opportunity to serve our community.

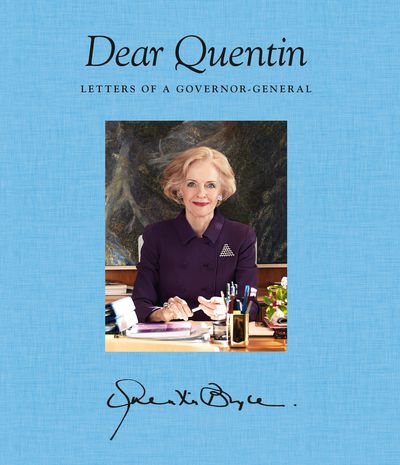

On a perfect autumn afternoon, 13 April 2008, the then Prime Minister, the Hon. Kevin Rudd, announced my appointment as Governor-General. It was a nerve-racking but lovely occasion at University House. There had been a shower of rain, the sun was out, soft clear light, red and gold leaves scattered on the pathway, wet and gleaming.I returned home, back to the last months of my term as Governor of Queensland. That September, my husband Michael and I went to Canberra for my swearing-in as twenty- fifth Governor-General by the Chief Justice of the High Court, Robert French AC, at Parliament House. Magnolia petals and white pear blossoms were falling in the breeze, pansies in wide pots. The correspondence began, which is the subject of this book. I was overwhelmed by letters and tidbits from everywhere. Generous spirit in spades; wisdom, kindness, delight shone through. Fathers wrote about their daughters, sons about their mothers, their pride in their achievements. Every message reached into my head and my heart, each one firming my determination to give my best every day, to make the most of a unique opportunity to serve our community.

I wanted to be a modern, inclusive GG, maintaining traditions and protocols that were significant and loved but being thoroughly contemporary at the same time. I planned my program carefully so I could listen to my fellow Australians, to learn more about them in every aspect of our nation. I was keen to show my support for people in remote and rural Australia, particularly in tough times. My first regional tour was to the Murray–Darling Basin to see for myself how people were coping with the drought, to let them know that city people care deeply about them.

There were many times of sadness during my Canberra years, tears held back, tears that fell.

That first official tour set a pattern for my letter writing. Thank-yous to those who welcomed us and ensured that our time in their place was constructive often started correspondences that have gone back and forth ever since.

In Deniliquin, women from rice farms gave me a box of their letters tied in purple ribbon, about the anxieties they cope with every day in the horrific drought. They wrote of their love for their community. People often express their innermost thoughts in writing in a way that they can’t or won’t speak about them in person, matters that bring tears of emotion if they try. I always feel complimented when I’m drawn into private and personal storytelling. An aide-de-camp commented, ‘I’m amazed by the things people tell you about themselves.’ It was a good thing to have the press along so we could draw attention to people and issues that needed it in the Murray–Darling, in Timor-Leste, in southern Africa and here at home. That often meant an increase in the mailbag.I’ve always enjoyed my correspondence with children: oh, the imagination, the adorable, amusing drawings, the portraits, the little bits and pieces tucked into envelopes. I appreciate their agreement to including them in this collection.It’s been a much harder job than I foresaw, making the selection from boxes and boxes of letters, metres of them, many skillfully recorded and archived but some stored in cupboards so jammed full that everything falls out onto the floor when I open them. Then I find myself sitting on the carpet, absorbed in heartwarming memories for hours.Each letter is precious to me, to open, to read and then to respond. Usually I did so at my desk in the quiet of early evening, often a time for reflection, for going inside oneself, music in the background.

There were many times of sadness during my Canberra years, tears held back, tears that fell. With a few exceptions, I have not included letters written to express sincere sympathy to people in awful grief. I could not know the depth of their sorrow in dreadful loss of a dearly loved one, but I wanted them to know that they were very much in the thoughts of Australians. I thought about my words carefully as I yearned for some way to give comfort.When I wrote the letters in this collection, I didn’t think for a moment that they would be read by anyone other than the people to whom they were addressed. I am grateful to each for their permission to include their letters to me. My writing to ask for this project started a fresh round of correspondence – like these first two letters from special correspondents Bunny Glover and Giordan Staines – and a fresh round of reflection on life during Yarralumla days.

Dear Quentin: Letters of a Governor-General by Quentin Bryce is out now.