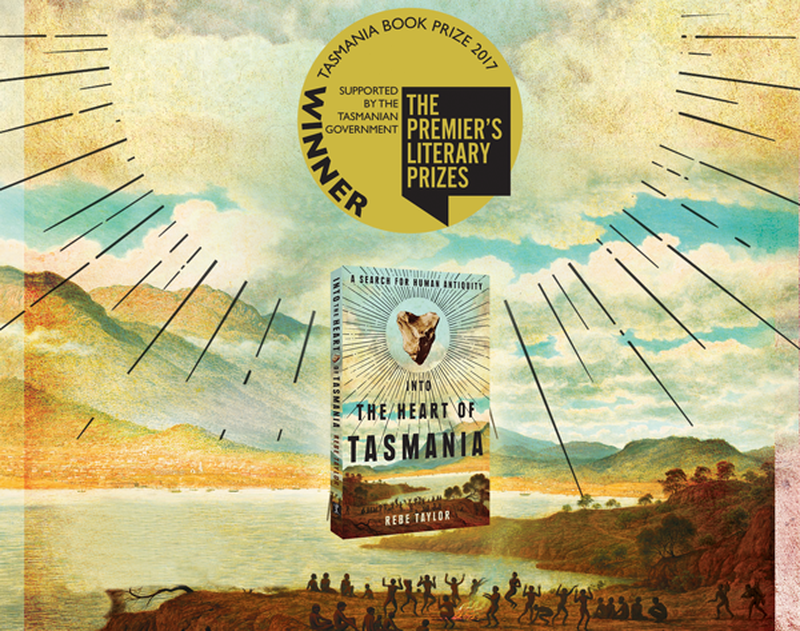

←Back to Into the Heart of Tasmania

An extract from “Into the Heart of Tasmania”

London, 1908

Ernest Westlake walked up the broad steps of the British Museum and, passing through that famous colonnade, stepped into a cramped and busy entrance hall. He did not follow the other visitors to see the Egyptian and Greek antiquities towering in the ground-floor galleries, but took the most direct route to where his interests lay. Up the Principal Staircase, lined with first-century Indian Buddhist carvings, he entered the Central Saloon. British Iron Age arrowheads, Bronze Age helmets and Neolithic stone axes regressed down to the prehistoric stone tools from British and French caves; made by the ‘races of men of whom we have no history’. The Early Stone Age was his particular enthusiasm, but knowing this room well he walked on, past the swords of the Anglo-Saxon Room and the tea sets in the Asiatic Saloon, until he reached the entrance to the Ethnographical Gallery.

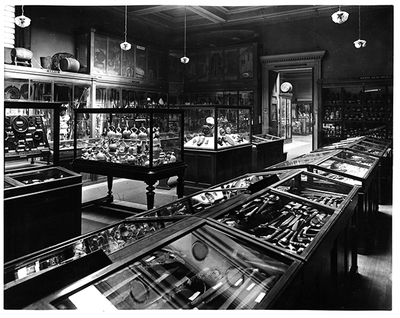

Five open-ended galleries stretched before him, extending almost the length of the eastern wing of the Museum’s upper floor. At once elongated and dense, the gallery reflected the spread of Empire. Glass cases reached up the walls and across the floors, each case packed with objects from the colonised world. Their origins were indicated in red on maps that hung from their doors; a guidebook sketched out their contents. On the right in the second and third rooms were artefacts from the ‘brown races’ of Micronesia and Polynesia: feather-work cloaks and helmets from Hawaii and jade paddle-shaped battleaxes from New Zealand. On the left, the collections from the ‘black races’ of the Pacific, Melanesia and Australia: boomerangs and spear throwers described as the ‘inventions among tribes who had no knowledge of the bow’. Near these wooden implements hung the ‘portrait of a Tasmanian belonging to a now extinct race’. A black man looked out from under a helmet of thick and matted hair, dressed in skins and shell necklaces, and holding a spear.

Then Westlake’s attention was arrested. It was a display he had not seen before, at least not this large and varied: a hundred stones, packed together under the peaked glass roof of a floor cabinet, where he could gaze down upon them. Some were no bigger than his thumbnail, others almost as big as his fist. They varied in shape — round, spherical, square, squat, tall, peaked and pointed — and were an assortment of colours: pearly white, sandy brown and even hard black. They had been broken for reasons that made the cabinet seem absurd: to crack a bone, skin a wallaby, prise open an oyster. The map on the cabinet indicated the island of Tasmania, southeast of mainland Australia. A few pasted labels offered the opaque names of towns and beaches: ‘Port Sorell’, ‘Ironhouse’, ‘Westwood’.

The pieces of stone made a sudden and inspiring impression upon him. They reminded him of stones he knew well, stones he had collected and held in his hands in a warm and quiet valley in the Auvergne region, central France. They shared the same rough, chipped angles and shapes, as if they had been made without plan or design. In France he had turned the stones over in his hands in wonder, unsure and excited, the sun on his back, the village church bell tolling in the distance: had he really found the tools of an unknown Stone Age race? That question had driven him to keep exploring. Westlake dug down to a geological depth he estimated to be 100,000 years old. He unearthed a mass of tools. French customs stopped him on his way home, complaining he was taking too much of ‘the soil of France’. He reduced the collection from 100,000 to 4000 artefacts. He was yet to present the evidence to the scientific community, but he could already hear the sceptics: the Auvergne stones were naturally broken rocks; it was beyond reason to claim artefacts of such antiquity and crudity could be man made.

The stones in front of him now would prove that it was possible. If the Tasmanians had made stone tools of such simplicity, why not also the early Europeans? Culture was evolutionary; even the most advanced civilisation had to begin somewhere. The Tasmanian Aborigines had evidently notprogressed; they had evidently been one of the most primitive races to have lived in modern times. But that made their tools so useful. They could authenticate his French artefacts. While the two cultures were admittedly remote in space and time, and the comparison between them could never be exact, it would be sufficiently close to prove the human origin of the European flint and to show that the level of culture was essentially the same.

Westlake knew instantly what he must do. It was a big decision. He was a widower and his children were still young. He was financially independent, but no longer prosperous. But at stake was determining the true depth of European human antiquity. He must then, at the earliest opportunity, travel to Tasmania and bring back his own collection of Aboriginal stone tools.

Pitt Rivers Museum Annexe, Oxford, January 2000

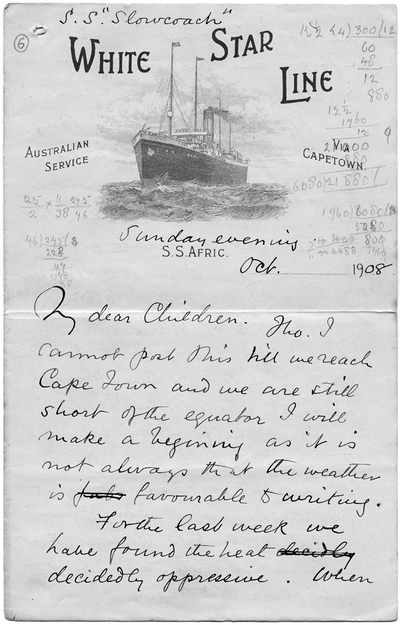

I am the only researcher in the small archives reading room. Its upstairs window reveals none of Oxford’s romantic parapets or domes, just a dull and wintry Banbury Road. The archivist says little except to complain about the cold and I am left largely alone in my task. I wonder where to begin. Which box, which folder? I know almost nothing of this archive, or of the man who created it. I decide upon his letters, for they begin at the start of Westlake’s journey to Tasmania, and are written to those he loved: ‘My dear Children’, he unfailingly addressed them. Aubrey, fifteen, and Margaret, twelve, were living variously at school or with their uncle and his family. For nineteen months Westlake wrote to them at least once a week: eighty-five letters in all as he travelled from the docks at Liverpool, to Melbourne, across Tasmania and back to London. In the absence of a diary, they record Westlake’s journey and research.

Westlake travelled to some of the remotest parts of Tasmania during the age of steam. It took seven hours to travel from Hobart to Launceston by train. Many places could be reached only by boat. Westlake had a tent and rode a bicycle, which was sometimes loaded with several kilograms of stones. He walked when the terrain was too rough, or when his bicycle broke down. He slept on sand hills, under bushes, in sheds and abandoned houses. There were many months when Westlake was in Hobart, reading in the archives, or in Launceston, photographing stone tools. Then his letters took a reflective turn, and I learned about his political ideas, religious beliefs, even his dreams.

After several weeks of reading and transcribing in the cold reading room, I felt I knew this odd, clever and tenacious 50-something-year-old man. Then I turned to his field books. Six of them, each small enough to fit into a pocket, their pages often dense and not always easy to read, as if the notes were written on a knee or a makeshift table. The first one, however, was rather dull, neat and sparse: a collection of lists, names and notes, mostly without context. But the second began suddenly in the middle of an intense and personal recollection recorded by Westlake in November 1908: Truganini, the ‘Last’ of the Tasmanian Aborigines, was remembered as laughing and crying and scared of dying. Other memories, just as striking, followed: stories passed down from the ‘Black War’ of 1826–34 filled with blood and shootings, more recent memories of the Aborigines incarcerated on Flinders Island in the Bass Strait, and at the old convict station at Oyster Cove, south of Hobart. The notebooks reveal a community coming to terms with a difficult past at the beginning of a new century in a recently Federated nation. They are filled with repentant shame, are also littered with attempts to apportion blame, but foremost they emphasise that the history of settlement has ended. Westlake was reminded over and over again by the settler descendants he spoke to that the Aborigines had all gone; they were ‘extinct’.

But then I encounter the voices of living Aboriginal people, first on the islands of the Bass Strait — the children and grandchildren of the Aboriginal women and their Straitsmen husbands who pioneered the settlements from the early nineteenth century — and then at Nicholls Rivulet, south of Hobart — the children of Fanny Smith (née Cochrane), who had passed away in 1905. The little notebooks were filled with Aboriginal knowledge: word lists and phrases, plant foods, hunting methods, medicines, and spiritual practices and beliefs.

Westlake called the Islanders and the Smith family ‘half-castes’. He thought that the language and cultural information they gave him was useful, and was more than he had expected to find, but he called it ‘second hand’. He assumed it did not belong to the people who spoke of it, but to their parents or grandparents; those whom Westlake called the ‘Blacks’, and whose culture he presumed was extinct and gone. But how was it gone when he was writing it down? Why was this knowledge passed on if not so it would be kept and continued?

Westlake’s imperception was typical, but his tenacity was unique. His determination to uncover every possible source of information about Tasmanian Aborigines led him to find what other researchers before him had missed. No one previously had made the effort to visit the Smith family. Few thought it was worth going to see the Islanders. Those who did had been met with a silence that they assumed was ignorance, but was in fact born from mistrust, and an agreement not to share their cultural knowledge with outsiders. But Westlake was not shunned by the Islanders or by the Smith family. His archive is the richest collection of Tasmanian Aboriginal culture formed in the twentieth century, and offers a way to see and understand how that culture was retained and practised. But has its value been recognised?

An archive dismissed

In 1991, NJB Plomley, a historian and honorary research associate at the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery in Launceston, published Westlake’s interview notes in the field books as The Westlake Papers. He edited Westlake’s notes substantially, cutting and moving text, but without indicating how, which makes his edition an unreliable source for researchers. Plomley also dismissed the value of Westlake’s interviews with Aboriginal people. He derogatively called them ‘half-castes’ and ‘mixed-bloods’. He thought the interviews with Fanny Smith’s children confirmed only that their mother had known ‘nothing of the Aboriginal way of life, and clearly had no wish to learn anything’. The interviews with the Bass Strait Islanders demonstrated to him that they had learned ‘nothing of the way of life of their Aboriginal forbears’. But for ‘few words’ the Aboriginal language had ‘clearly been lost, as well as almost everything else, quite early’.

Plomley’s reading of Westlake’s papers was coloured by recent politics. From the 1970s the Tasmanian Aboriginal community began to publicly and stridently fight for rights to land and education, for the return of their ancestors’ bodies from museums, and for recognition that they were not extinct. Plomley was a conservative scholar who had spent his career researching their history. He did not believe they had the right to call themselves ‘Aboriginal’. He likened their ceremonial cremation of repatriated ancestral remains to the violence of the white settlers towards Aborigines on the early frontier. The invective seems out of place in the introduction to Westlake’s papers, but Plomley did not want to miss the opportunity to add his voice to a wider debate between Tasmanian Aboriginal people and the scholars who studied their cultural history.

Much of the hostility had begun with a controversy stirred by an Australian archaeologist. In 1965, Rhys Jones deduced that the first Tasmanian Aborigines had reached their island by foot, before the end of the last Ice Age, 10,000 to 12,000 years ago, when rising seas had created the Bass Strait. By 1977, Jones proposed that isolation had caused the Tasmanian Aboriginal culture to simplify. Then, as the narrator of the popular 1978 film The Last Tasmanian, Jones drew a figurative parallel between simplification and extinction, asking even if Europeans had never discovered Tasmania, had the Aborigines nonetheless been ‘doomed’ by the devastating effects of isolation? The idea caused a fracture between the Tasmanian Aboriginal community and the academy that lasted for decades.

Jones’s controversial thesis had an important connection to Westlake’s interviews. The notion of simplification hinged foremost on two supposed cultural losses: the ability to catch fish with scales and the art of making fire. But both Aboriginal and settler Tasmanians described knowledge of these skills repeatedly to Westlake, as Jones knew. He had been the first Australian scholar to study Westlake’s collections in the Pitt Rivers Museum. He later wrote that Westlake helped lay ‘the foundations for Tasmanian field archaeology’. It was perhaps the sheer size of the stone tools collection that prompted the compliment, for Jones dismissed Westlake’s evolutionary theory and his archive. He did, however, first read Westlake’s notebooks carefully. While Westlake never wrote down his questions, Jones had known that he had often asked, ‘Did the Tasmanians know how to make fire …?’ Jones disregarded the answers because they dated over a century after first contact.

Jones was adhering to the parameters of his discipline. Historical sources had to be largely unaffected by the ‘tide of history’ for archaeologists to trust they could inform the deeper past. The requirement troubled Westlake, too. He was pleased and surprised by the wealth of information he was given in Tasmania, but he never saw it as a ‘pure’ or truly authentic record of Aboriginal culture. That, he assumed, had gone.

A new lifeworld

The threads of traditional continuity are present in Westlake’s papers. Many of the descriptions of cultural practice, including fishing and fire making, are echoed in far earlier historical records. What was changed by 1908 was the context of those traditions. Tasmanian Aboriginal people had indeed adapted, often in order to survive and endure.

Despite these changes, generations of Tasmanian Aborigines did hand down important traditional knowledge that present-day descendants continue to remember. Tasmanian Elder Patsy Cameron in her 2011 book Grease and Ochre, describes that out of her ancestral history — the Aboriginal women and their white husbands who pioneered the Bass Strait Island settlements — there emerged a new generation and community defined not by loss, but by the ‘transformative power’ of their island environment and of the ‘blending’ of their cultures, economies and traditions. This fusion created what Cameron calls a ‘new lifeworld’.

Westlake’s interviews offer insight into that ‘lifeworld’ and to the handed-down traditional knowledge, revealing the ways Tasmanian Aboriginal cultural practices in both the islands and the Nicholls Rivulet communities had been maintained. But this realisation has only been possible to explain with the guidance of Tasmanian Aboriginal people. They include, among others, those whose ancestors pioneered the Bass Strait Islands: Patsy Cameron, Jim Everett and Buck (Brendan) Brown, and the descendants of Fanny Smith, Cheryl Mundy and Clinton Mundy. Their guidance has been crucial, for it has meant perceiving that which Westlake failed to see.

Westlake saw neither the depth of Tasmanian Aboriginal antiquity nor the wealth of its continued existence because he was looking for something else: the artefacts and facts that would validate an imagined phase of European history. Westlake did not understand the true value of his collections. In noting the discord between his intention and his actual achievement something is learned.

Westlake’s papers have taught me to ask myself: How do I see the past? How do I see Aboriginal peoples and cultures in the archive, or indeed, in the present? Am I looking in order to prove a point? To advance my discipline? To educate my fellow Australians? To even chastise them? None of these things are necessarily wrong, but it is important to consider how these goals might colour my vision. It is important to ask myself: Can I look into the past, or even at the present, can I cross cultures, and actually learn something new? Can I see what is before me? Can I actually see a new ‘lifeworld’?

It has been a long journey just to get to the point of asking these questions. But then, a journey that follows Westlake is full of curious and circuitous turns.