Read the Extract: Modern Love

Sunday and John Reed: the Great Australian Love Story

Part romance, part tragedy, Modern Love: The Lives of John & Sunday Reed explores the complex lives of these champions of successive generations of Australian artists and writers. The book details their artistic endeavours and passionate personal entanglements.

Sunday, before John Reed

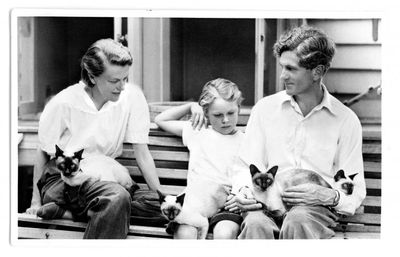

Sunday Baillieu was worldly but damaged, and John Reed was just coming into his own when they met in 1930. Twenty-four and twenty-eight respectively, they came from the same privileged social echelon and shared a sense of rebellion against their expected paths. A solicitor with alternative views, John was strikingly handsome, with an aristocratic bearing and a calm disposition. Sunday, recently separated from a miscreant first husband, felt a little vulnerable in his presence and was yet to display her more capricious temperament. Physically she was slim and fair, possessing an uncommon beauty and an undeniable allure. They were reserved and slightly hesitant with each other in the early days of their courtship, although each recognised a kindred spirit, someone with a similar appetite for new experiences who sought a deeper fulfilment than life had offered thus far. Displaying the disregard for social proprieties that would go on to characterise their partnership, they would live together within the year.

While John recalled that ‘it was not a dramatic meeting ... and Sunday did not “change my life”’, his sister Cynthia quickly sensed the depth of his feelings, quipping that it seemed as if he had been struck with ‘the love disease’. Indeed, Sunday’s impact was perhaps more decisive than John was willing to admit. Neither of them had come to this point in their lives via an easy journey.

Sunday and John Reed meet for the first time

Sunday was, John acknowledged, well-versed in modern literature when he encountered her. However, her direct contact with art—not-withstanding DH Lawrence’s notorious exhibition of erotic drawings, which she had seen in London in 1929—had hitherto been limited to the classics and the conventional: the paintings of feted artist and family friend Arthur Streeton, her portrait sitting with Agnes Goodsir in Paris, and the European Old Masters, though she had also made the pilgrimage to Monet’s Giverny. Her blossoming romance with John saw her welcomed into a circle of creative and energetic friends for whom art, ideas and intensity of living were the norm. Sunday understood the significance of John’s growing feeling for modern art and pushed him to explain and clarify his thoughts and reactions.

He remembered the profound, vitalising effect she had on him:

‘So far as I was concerned, two things happened: I responded to her as a person, and at the same time she challenged me in a way no one else had ever done’.

This push–pull dynamic of their interaction was at the very heart of the relationship, becoming the impetus behind the con- tributions that John and Sunday would eventually make to Australian culture and history. Each was extended and elevated as a result of their connection, the whole greater than the sum of the parts.

Sunday and John Reed get married

By mid-1931 Sunday’s divorce from her husband Leonard Quinn had been finalised and she and John wasted no time announcing their engagement in October. They were wed at St Paul’s Cathedral, Melbourne, on 13 January 1932 in a private ceremony. As Sunday had been married before, the union was not recorded in the cathedral’s official register. The couple instead took their vows in a side chapel after the bride’s father, Arthur Baillieu, made a substantial donation towards St Paul’s future building program, subsidising the completion of the two great spires.

The reception was held at Vailima, Sunday’s aunt Amy Shackell’s house in Toorak, where a pink striped marquee was erected in the garden. Sunday wore a contemporary gown of chalk-white chiffon—‘soft and dreamy and just right’, according to her mother, Ethel—with a fur pelerine and a broad-brimmed hat of dressed, white panama straw serving as a ‘halo’ for her face. The wedding cake was a gift from one of the guests and firmly in the sights of John’s dog Karel, who reportedly attempted to make off with it. Writing to the newlyweds the following day, Ethel declared the day ‘went beautifully like silver bells’, Sunday never looking sweeter or lovelier and John giving a great little speech. Photographs were few, but Sunday’s younger brother Everard captured proceedings on his cinecamera, making it a most modern a air.

Arthur and Ethel Baillieu must have been relieved, if not delighted, to see their daughter in John’s safe hands. He was an eminently suitable husband: educated, professional, sensible, monied and, most of all, he seemed to have all the patience in the world for Sunday’s emotional fragility and fickleness. John’s father, Henry Reed, was unlikely to have felt an equivalent satisfaction. A nouveau-riche and barren divorcee, Sunday can hardly have seemed a desirable catch, in spite of any agreeable personal attributes. It was Cynthia who warmed most to the new member of the family. After a period in England on a program of cultural self-education, then a year in Germany where she worked as a nanny, the youngest Reed daughter returned to Melbourne in time for John and Sunday’s wedding. Already close to her brother, Cynthia would go on to develop an intense friendship with Sunday, who was similarly cultivated and well-travelled, and bore an uncanny resemblance to her sister-in-law. Cynthia would play an important role in the couple’s early relationship.

Friends of Sunday and John Reed come together

It was through Cynthia that John and Sunday met and befriended an eclectic group of people united by their interest in art of the times. They were particularly fond of Herbert Vere Evatt, a former ‘legal meteor’ of the New South Wales Bar. Later a federal Member of Parliament, at the time he was on the Bench of the High Court of Australia—the youngest justice ever appointed.6 Cynthia dubbed him ‘Judgie’ and the Reeds knew him as ‘Bert’, though history has remembered him as ‘Doc’. Evatt’s wife, Mary Alice, was a supporter of Sunday and John Reed on their wedding day,

Other friends of Cynthia, John and Sunday in the early 1930s included the art critic and pundit Basil Burdett; the newspaper proprietor Keith Murdoch and his wife Elisabeth; the writer Joan Lindsay and her husband Daryl Lindsay, an artist; and the Collins Street dentist and art collector Vivian Ebbott and his wife Sunny. But perhaps the most important of the introductions Cynthia made to the Reeds was a young painter by the name of Sam Atyeo.

The meeting with Atyeo in the first year of their marriage was the start of something significant in the Reeds’ lives. They felt a strong personal connection with him and before long he became their most intimate friend. With rugged rather than good looks and a certain roughness around the edges, Atyeo was nonetheless charismatic. His verve and appetite for life were infectious, and contact with his art and the process of its making made them feel they were participating in an endeavour that was not only creative but also tremendously exciting and important. Their affinity had other dimensions as well. Atyeo would join John and Sunday in their first experiment with an alternative model of relationship, one that would come to define the terms of their marriage: what the French discreetly call a ménage à trois.

Modern Love: The Lives of John & Sunday Reed is a double biography by Lesley Harding and Kendrah Morgan, a co-publication from MUP’s Miegunyah Press, the State Library of Victoria and the Heide Museum of Modern Art.