Steve Bracks in conversation with Bernard Collaery: Opening Remarks by the Hon Steve Bracks AO

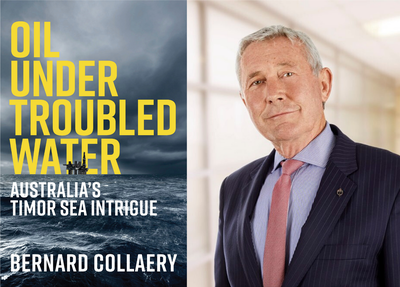

On March 25th, we held the virtual event 'Steve Bracks AC in conversation with Bernard Collaery' in partnership with Readings Bookshop to launch Oil Under Troubled Water. Below is a transcript of the opening speech made by the Hon Steve Bracks AO.

In this time of the corona virus it is difficult to focus on anything else. Our lives have been disrupted in so many ways.

Yet the wheels of our ‘justice system’ and our intelligence agencies continue to turn. The lives of Bernard Collaery and the ASIS agent known only as Witness K, were dramatically disrupted in December 2013 when the home of Witness K, and Bernard’s law chambers, both in Canberra, were raided by ASIO and the Australian Federal Police.

The raids occurred on the eve of a hearing at the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague in the Netherlands. The arbitration was initiated by Timor-Leste which was seeking to have a Timor Sea maritime boundary treaty negotiated with Australia in 2004, known as CMATS, declared void because Australia acted in bad-faith by bugging the room used by the Timorese negotiators.

The use of state-of-the-art spy-craft by Australia against the newly emerging nation of Timor-Leste was an unconscionable betrayal. The Timorese considered Australia a friend. Many Timorese believed Australia owed Timor a debt of honour. When Australian, British and Dutch troops invaded neutral Portuguese Timor in 1942 during World War II, the Japanese soon followed. The Australian troops were kept alive by Timorese guides and villagers, before they were evacuated a year later.

Fifty thousand Timorese died in the course of the war. A war Australia helped bring to their doorstep. “We will never forget you” we said – but we did.

Bernard knows that story all too well. In his riveting book, he recounts how he first heard about Timor-Leste in his final years as a law student at Sydney University when he received “some specialised training from an Australian intelligence agency” and one of the trainers spoke passionately about the Timorese people.

Yet despite this debt of honour, the Australian government betrayed the Timorese people over and over again. In 1975 the Whitlam Labor government encouraged Indonesia to invade what was then Portuguese Timor. In 1978 the Fraser Liberal Coalition government ignored credible reports of deliberate mass starvation and on-going atrocities and became the first and only western government to formally recognise Indonesia’s sovereignty in East Timor. Why? Because it was an inevitable consequence of negotiating a maritime boundary with Indonesia between Australia and East Timor.

In 1989 the Hawke Labor government signed the Timor Gap Treaty that gave Australia rights to oil and gas on the Timor side of the median line - infamously, signing the treaty in a jet over the Timor Sea as foreign ministers Gareth Evans and Ali Alitas drank champagne for the cameras.

In 1999 the Howard government supported autonomy within Indonesia – not independence. Foreign minister Alexander Downer initially argued against sending in peacekeepers. And then as Bernard describes in fascinating detail, the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs, led with enthusiasm by Downer, succeeded in manipulating the UN administration into a series of agreements and treaties that denied the Timorese their rights under international law to a median line boundary in the Timor Sea.

One of the most intriguing aspects of Bernard’s book is his forensic examination of how DFAT, and minister Downer, to use Bernard’s words, “connived to hide from the United Nations and the Timorese the presence of massive quantities of helium gas”, produced as a by-product of processing the Bayu Undan gas in Darwin.

Then, as if we had not exploited our power advantage enough, as if we had not betrayed the Timorese enough, in 2004 ASIS, that was under his jurisdiction of minister Downer, secreted listening devices in the room being used by the Timorese during complex negotiations over rights to billions of dollars of oil and gas in the Timor Sea.

It would have been obvious to anyone visiting Dili in 2004 that the Timorese were struggling to provide basic education and health services. The power went out numerous times a day. Water was undrinkable. Poverty endemic.

Remember also that in 2004, when the bugging occurred, terrorist group Jemaah Islamiyah in Indonesia was a serious threat to Australia’s national security.

It is no wonder that some, if not all, of the ASIS officers directed to install listening devices in the cabinet room in Dili would have been shocked and appalled at what they were being asked to do. One of the many problems Bernard’s book illustrates is that our intelligence agencies are a law unto themselves.

The ministers with responsibility for our intelligence agencies, currently Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, Home Affairs minister Peter Dutton, and Attorney-General Christian Porter have unfettered power. There is no parliamentary oversight of intelligence operations like there is the US, Canada and the UK.

I wholeheartedly endorse Bernard’s conclusions that the “Timor-Leste story illustrates a wider malaise in Australian democracy”. The heads of the various intelligence organisations rotate around the top jobs. Hence David Irvine, the head of ASIS at the time of the 2004 bugging operation, was head of ASIO at the time of the Canberra raids on Bernard and Witness K in 2013. That was when the Howard government used national security laws introduced to combat terrorism to seize legally privileged documents from Bernard Collaery’s law chambers. That was a breach of diplomatic immunity and lawyer client privilege.

When Australia refused requests to return the documents, Timor-Leste successfully took action against Australia in the general division of the International Court of Justice. In April 2016, Timor-Leste became the first nation to invoke the compulsory conciliation provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Australia lost a preliminary argument that the Commission had no jurisdiction to conciliate the Timor Sea dispute. In the process of the conciliation, Australia succeeded in getting Timor-Leste to withdraw from the spying arbitration proceedings and in return finally committed to negotiate a permanent maritime boundary.

In August last year Scott Morrison became the first prime minister to visit Timor-Leste in a decade. He was there to join in the celebrations marking the 20th anniversary of the historic vote for independence from Indonesia. He was also there to finally sign a median line-based Timor Sea treaty.

I was at the ceremony with my friend, and long-time Timor champion, Harold Mitchell. It was surreal sitting there in the sweltering heat watching the Australian prime minister and officials gathered in the forecourt of the very building Australia bugged 14 years earlier. I have no doubt that if not for the revelation of the illegal espionage operation, Australia would not have agreed to median line boundary in the Timor Sea.

But that treaty, in part was yet another betrayal of the Timorese people. There was no provision for repatriation – for Timor-Leste to be paid back the billions Australia has banked from oil and gas fields we now acknowledge are in Timorese waters. As Bernard concludes in Oil Under Troubled Water there must be an “exemplary process of recognition of past wrongs affecting East Timor, including restitution”. He also argues for a clean out of public servants who have dealt with the Timor issue over the years. I also endorse Bernard’s call for ASIS to have independent statutory status and to be subject to appropriate Cabinet and parliamentary scrutiny.

Before I finish and hand over the zoom microphone to Bernard, I’d like to thank him for his bravery and his strong moral compass. The prosecution of he, and Witness K, is political. The only good thing to come out of it may be, that Downer and Howard are called to account for their actions leading to the despicable Dili spying operation. I have no doubt Xanana Gusmao will have a very interesting story to tell if he is called to the stand.

Thank you.