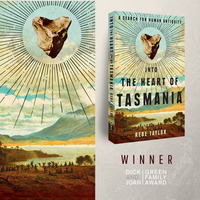

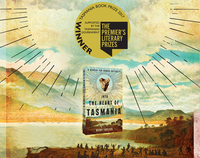

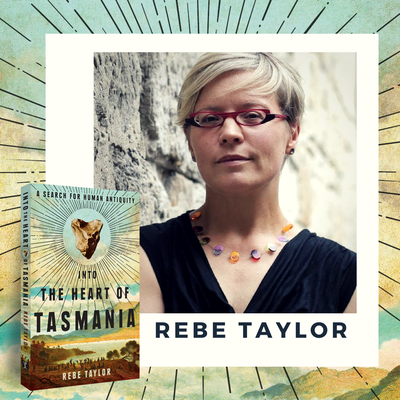

Q & A with Rebe Taylor - Author of Into the Heart of Tasmania

Rebe Taylor reveals the beating heart of Tasmania and the history that has never ended.

Into the Heart of Tasmania is an award-winning book telling the story of Ernest Westlake, and his ambition to rewrite the history of human culture inspires an exploration of the controversy stirred by Tasmanian Aboriginal history. The book has won the inaurgural Dick and Joan Green Award for Tasmanian History in 2018, the 2017 Tasmanian Book Prize, and the 2017 Queensland Literary Award History Book Prize.

Rebe Taylor is a historian specialising in Tasmanian anthropology and archaelogy. Into the Heart of Tasmania is part of Rebe's continuing effort to understand the history of Tasmanian Aboriginal diaspora, loss, rediscovery and endurance.

MUP spoke with Rebe about what inspired her research, the most important lessons she learnt, and the future of the Tasmanian Aboriginal Community.

Q–In Into The Heart of Tasmania you demonstrate a great and resounding cultural respect for the Tasmanian Aboriginal community, including a note that shows insight into their relationship with the land and history. Who did you work with, or consult in the production of your work?

Well, I think they deserve a great and resounding respect, and if I’ve come close to showing that, then that is the best mark of success. I first encountered Tasmanian Aboriginal history a long way from Tasmania; on a sheep farm on Kangaroo Island, South Australia, when I was about seven years old. I remember being told that the farm had been the home of a man who had arrived long before the official settlement of South Australia. He had lived with a Tasmanian Aboriginal woman, who was taken there as part of the sealing industry. She was remembered only as “Betty”, but she had children, and descendants whom I later met. In fact, their story became my first book (Unearthed).

It was later that I decided to go to Tasmania as part of my PhD research, and it was then that I first met Patsy Cameron, Jim Everett and Greg Lehman who, years later and after much other writing, helped me with Into the Heart of Tasmania. They were very patient with me, and my many questions. But I remember it was Jim who taught me one of the toughest and best lessons. It wasn’t just how to clean mutton birds (there is a picture of me cleaning birds in the book – I wasn’t very good at it!). Jim told me to put my notebook down, and to listen, and look at the country and culture. He said to stop being a researcher. That was when I really began to learn – and the first lesson was how little I knew. I haven’t moved much beyond that first lesson, really!

Q–In a previous interview with Tasmanian Writers Centre, you said: “When I first went to the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery I remember seeing a diorama of an Aboriginal ‘family’ (child, father and mother) standing behind glass, with a plastic crayfish on a fire. There was no mention of their continuing culture or community.”

Have you noticed Australian/Tasmanian cultural institutions changing their approach to showcasing members of their communities and Tasmanian history?

Yes, enormously, and perhaps none more than the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. This is, after all, the institution that displayed Trukanini’s (Truganini’s) skeleton, even when doing so was against her express wishes, and in fact even against the Act that had allowed her remains to be disinterred in 1878. But since the 1990s, this museum has had a permanent exhibition celebrating the struggle of the Tasmanian Aboriginal people for their land and for the right to be recognised as a living people – not an extinct race. It also includes the first canoe built by Tasmanian Aboriginal men in 180 years, as well as baskets and shell necklaces made by Tasmanian Aboriginal women. The more recent First Tasmanians exhibition at Launceston’s Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery is also amazing in this way, and it was a project managed by Greg Lehman, a Tasmanian Aboriginal man in consultation with his community. This change is so heartening and important.

Q– Tell us about your subject, Ernest Westlake. How did you come by his work, and how did it evolve into a book?

My PhD was on the representation of Tasmanian Aboriginal culture in anthropology and archaeology. I read as much as I could from the scientists who had many theories about the Aborigines, and who had formed collections of their tools and human remains. One of these scientists was Ernest Westlake, but he was very little known and almost nothing was written by him or about him. When an opportunity came to go to Oxford on exchange, I decided to examine his papers held in the Pitt Rivers Museum. Also housed there were more than 13,000 stone tools Westlake had removed from Tasmania in 1908-1909. The five boxes of his papers included notebooks from interviews with many Tasmanians, including Aborigines. But the first thing I read were the letters to his two children, who were at boarding school while he travelled and collected. The letters were very personal – written to those Westlake loved – and they also detailed his journeys across Tasmania in the form of a diary. I was instantly absorbed, and wanted to know him better.

Westlake was an extraordinary, eccentric and passionate man whose ideas about anthropology and human antiquity were misguided and long since obsolete, but through his eyes we can see what he was never able to: the living culture of the Tasmanian Aboriginal people.

Q– What is it like to be part of the Tasmanian writing community? What do you think are the biggest challenges currently facing the Tasmanian, and larger Australian, literary community?

Well, I’m not sure I can yet call myself a Tasmanian as I’ve not yet moved to the island…but if I could count myself among that writing community, I’d be proud. Tasmania has produced many excellent writers, including some well-known and acclaimed historians, like Henry Reynolds, Marilyn Lake, Cassandra Pybus and James Boyce.

I’m sure the biggest challenges for the Tasmanian and Australian literary community are what they have always been: how to find the time to write. For time means finding money, and money is always hard to come by if it is from ones writing!

Q– What is your writing studio like? In your book, you mentioned a ‘converted garden shed’. Tell us more!

It is a converted garden shed. My desk looks out onto a large fig tree, which lets me check the seasons which often causes me to worry that I’m behind in my deadlines. The former shed is very close to three of my neighbours’ fences, so I often hear dogs, one neighbour’s ukulele, and sometimes a bit of chatter. I hate leaf blowers! One wall is lined with shelves. One wall is free to use for practicing yoga which I do most mornings. The journey across the garden to open the door means I leave behind the washing up or the children or whatever is probably actually more important than writing, so it often gets put off. And sometimes it is too hot or cold there. But it is where I am most productive.

Q–What has been your favourite part of book tours?

I am not sure I’ve ever really ‘toured’ except going to writers’ festivals and doing a series of events in Tasmania. I love meeting people, especially other writers, and I love it when my partner comes and we can enjoy the amazing vibe of people loving ideas, wine and talking. But I have to admit the best part of all is coming home. There is a reason I can spend hours alone in a converted garden shed: I like it!