Christina Stead and her life in Letters

Christina Stead remains one of Australia's most illustrious writers

Christina Stead remains one of Australia's most illustrious writers. She was also close with numerous influential literary figures, such as Dorothy Green, Stanley Burnshaw, Ettore Rella, Nettie Palmer, Clem Christesen, Elizabeth Harrower and A.D. Hope. These significant friendships endured throughout her life and her career, and have been canvassed and considered within her correspondence with them.

Christina Stead’s letters, with their awkward Australian bones, their cosmopolitan sensibility and their ‘‘intelligent ferocity’’, cannot help but draw us in. Talking into the Typewriter: Selected letters (1973–1983) is the second volume in the collection of letters, the first being A Web of Friendship.

Together they comprise a collection of Christina Stead's letters from the year 1928, until her death in 1983. Below is an edited extract from Hilary McPhee's introduction to Talking into the Typewriter.

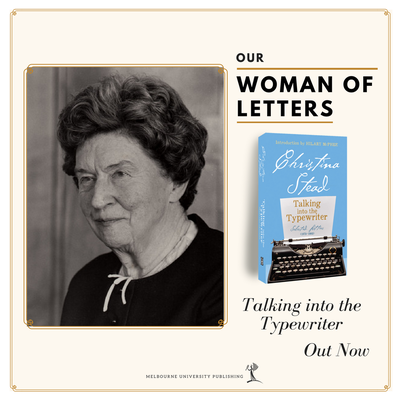

A few months before Christina Stead died in April 1983, a photographer from Mode magazine captured something of the force field of her. It could not have been an easy occasion. There she sits on a broad concrete step in a Sydney garden, dressed for the event in a dark trouser suit and white frothy blouse, a mannish straw hat tilted on her head. Stead is looking piercingly at the camera like the fierce old bird she was.

Christina Stead didn’t grow old gracefully. Why would she? How could she?

Very much alone, in poor health, anxious always about money, she is in her early seventies when this last fine selection of her letters begins. Stead was still living in England, in the crumbling half-house at 12A Elmers Court, Surbiton, Surrey, which she’d shared for many years with her writer husband Bill Blake.

Stead had visited her family in Sydney after Bill died in 1968. She stayed for eighteen months, drinking too much, hating the attention as celebrity took hold, mocking Australian academia and provincialism, missing her pals in New York. But she made good friends of writers and editors such as Elizabeth Harrower, Clem and Nina Christesen, Michael Wilding, Judah and Tyrell Waten and Dorothy Green. Aware that she’d likely have to return to her family to live and almost certainly to die, Stead paid for an extension to be built on to her youngest brother’s house in the outer-Sydney suburb of Hurstville.

‘What am I doing?’ Stead wrote to her ‘darling girl’, Nadine Mendelson, in 1977. ‘Nothing but empty nothing ... it looks as if I cannot get on alone, but need a life companion. The family (mine) is good to me, really better than I might expect, after my having been away for nearly forty-five years; but just the same the only thing for me is love between man and woman and that is the only thing that makes me work. I don’t care at all for all the accidents of life, that is publication, people visiting, episodes at universities (writer-in-residence—it is still going on). It is all nothing, nothing.’

In this last decade, Stead’s most unvarnished letters are to old friends, longing to see them, anxious about their health, reporting on her own recurring heart problems, describing the life she was trying to build in a country they will never see.

When Dorothy Green offered Stead her house in Canberra for a while, she moved with alacrity out of what she had begun describing as her ‘sheltered workshop’. It was the mid 1970s. Whitlam was in government, and the capital was more politically interesting, more sophisticated than she’d expected.

As the first recipient of Patrick White’s Award for Distinguished Writers, and with small pensions from the US and the UK, Stead’s money worries eased. A literary colossus, she was invited to universities up and down the east coast and her letters describe long periods of being happy and sociable. But to some of her friends from her old New York life, she confided.

‘Nugget’ Coombs, Governor of the Reserve Bank, former Chancellor of ANU, was much loved, even fixated upon. The many letters to her ‘Dear Cole’ were written by a woman smitten but anxious not to make a fool of herself. Or to reprimand. When Coombs, also living like Stead, in University House at ANU, had more important meetings to go to, friends to see, ‘I came away (about 11.30 pm) in a strange state of mind—slightly awestruck or respectful or something I have never felt before (with him). He is immensely shrewd ... ’

Coombs broadened her knowledge of Australia, involved her in constitutional reform after Whitlam’s dismissal in 1975, sent her papers on anthropology and on Aboriginal issues. She engaged with the homeland movement of the day, approving when the Pitjatjanjara people courteously asked an American photographer, a friend of hers, to leave their lands. ‘I think this is good news. Do people want to be visited as a curiosity?’

‘I am very welcome and well-received here, Ettore, but they are not “my own”. They are not the brothers and sisters I picked up along the way of my life. Whom I miss.’

When ‘John A. Dillaway Snr.’ read an interview with Stead describing the pain of separation from old friends, he wrote to her from ‘his waterside village at Hawks Nest’. A flirtatious late-night correspondence began ‘mainly about birds, insects, snails, jokes, tricks, fancies—he had an intimate witty feeling for language and wrote that sort of French ... part English even some Russian jokes.’ Only three months later, Dillaway died and Stead mourned him deeply.

Christina Stead’s last years were lonely and debilitating

She lost things, destroyed papers, burnt letters as she moved from Hurstville to friends’ spare bedrooms and university colleges. She was difficult to help and awkward to house, setting up her typewriter wherever she could, hoping to work, in reality exhuming old work and answering correspondence. Her teeth hurt so she preferred to eat in private, drinking to cope.

When Monash academic and writer Mary Lord offered Stead a home with her in Melbourne’s Hartwell in 1979, Stead writes to Ron and Dorothy Geering to explain her recent silence,

‘Well at first—I didn’t have a typewriter, then I didn’t have a ribbon (Mary Lord got me one in a used typewriter boutique), then I didn’t have a desk (Mary Lord gave me one for my birthday) ... I like it here; Mary and I get on.’

Stories are told and retold for friends by a genius of a storyteller, making herself up, putting a spin on things, downplaying her night owl miseries, her terror of being unable to work, yearning for the perfect setting with a soulmate where she can set up her desk and pour forth.

Mary Lord was heroic. Many years later she described a family Christmas party when Stead followed her around the house before the guests arrived, in a kind of panic, blowing out the candles and turning on all the lights. The dark bothered her.

Literary trustees are vested with a good deal of discretion. Their role is not only to safeguard a writer’s copyrights and secure a home for their papers, it is, consciously or otherwise, to manage the context, dilute the gossip, and show the writer, if not in the best light, at least in a sympathetic one.

Stead’s letters were compiled for publication after her death by her patient friend, Professor Ron Geering, appointed as literary trustee by Stead in 1980. She left him a trunk of papers, fragments of stories and an agreement with the NLA to negotiate, calling him ‘Ron-Ron’ as she leant ever more heavily on him and his wife ‘Doro’, for advice, for temporary accommodation, especially at Christmas.

Stead was as fortunate in her literary trustee as she was in her biographers, Chris Williams and Hazel Rowley. Talking into the Typewriter, Christina Stead’s last volume of letters, is something of a mirage. Stories are told and retold for friends by a genius of a storyteller, making herself up, putting a spin on things, downplaying her night owl miseries, her terror of being unable to work, yearning for the perfect setting with a soulmate where she can set up her desk and pour forth.

By April 1980 Stead was back in Canberra with an Emeritus Fellowship supporting her residency in University House, near again to her beloved Nugget Coombs. This was probably her happiest time in Australia. Her friends included Jack and Clare Golson, Rosemary Dobson, Alec Bolton and Nick Jose. The small residential quadrangle also housed for a while Gough and Margaret Whitlam. ‘Gough is a beautiful man ... when he enters a room he changes it with his natural presence’ she wrote to her old friend and publisher Stanley Burnshaw on Bill Blake’s birthday.

Christina Stead was infamously difficult to interview

But publishers, feminists and journalists got very short shrift— especially young ones. In her introduction to Letty Fox: Her Luck (Miegunyah Press, 2011), Carmen Callil recalls a painful meeting with Stead in 1980 when, as a young publisher, she sought to reprint Stead’s novels in Virago’s new list of Modern Classics. The novels are full of wondrous examples of young women— full of sap, breaking the rules, surviving on their wits—in real life they always riled her. Not until Stead read in 1980 Laurie Clancy’s ‘intense, inward study’ of The Man Who Loved Children and For Love Alone did she admit ‘for the first time’ to seeing aspects of herself.

She was then living with her youngest sister in Wollongong. She had had a fall at University House, the cleaning staff had complained about the empty bottles, and her doctors at Canberra Hospital insisted that she live with family.

This she did reluctantly, until Mary Lord again came to the rescue ringing a younger doctor friend who had treated her before.

Helena Berenson took Christina Stead in to live with her and her husband, Geoff Davis, in their Annandale house, for the last few weeks of her life. Both were doctors working different hours so Stead was not alone. They cared for her tenderly, sometimes speaking in her beloved Yiddish. There were birds to watch in the small garden and Helena, a gifted pianist, played Stead’s favourite Mozart in the afternoons. In the dark hours they could hear Stead at her typewriter in the dining room.

Hilary McPhee AO is a publisher, editor and writer. She was Chair of the Australia Council and the Major Organizations Board 1994-7. Her books include Other Peoples’ Words, Wordlines, and Memoirs of a Young Bastard, the Diaries of Tim Burstall.

This is her introduction to Talking into the Typewriter: Selected Letters (1973–1983) by Christina Stead (Miegunyah Press, $29.99).